The market for mindfulness

When my mom told me last month that she started doing daily meditations on Headspace, I knew for sure we’d reached peak mindfulness. She’s a devout Christian who was long skeptical of the practice’s Buddhist roots. I never expected she would to try it out. But it’s almost unavoidable. Mindfulness workshops at work, yoga studios in the airport, enough meditation apps to fill your smartphone’s storage.

Until recently, I assumed that mindfulness was a relatively new development in American life—a product of the West’s recent obsession with yoga and Eastern mysticism. Now, I’m beginning to realize that this is not our first rodeo. What can we learn from previous revolutions in thought, and how might we make sense of the underlying patterns in our ideological evolution?

Calvinism and its discontents

Take a little trip with me back to the 1800s, when the Calvinist spirit reigned supreme in America. Calvinism, a branch of Protestantism, urged its followers to constantly monitor their thoughts and root out the evil within. Calvinists were supposed to regularly subject “their hearts to scrutiny for signs of sin or self-indulgence” in order to improve their relationship with God. In Bright Sided: How Positive Thinking is Undermining America, Barbara Einreich describes how taxing this was for many believers.

“The weight of Calvinism, with its demand for perpetual effort and self-examination … could be unbearable.” Crushed by the burden of their own awareness, Calvinists often succumbed to a condition they called “invalidism"—a debilitating idleness that we might refer to as major depression.

Today, America’s mindful meditators are encouraged to practice introspection and pay close attention to their thoughts. Their end goals are quite different than Calvinism, but the process isn’t all that different. The Calvinists were trying to avoid the fires of hell; meditators are striving for increased self-awareness, self-control, and sometimes even improved productivity. In the ever-popular Headspace app, Andy (the narrator) uses a meteorological metaphor to explain how this works. You are like the blue sky, and your thoughts are the clouds. You can watch your thoughts as they float in and out of your awareness—they are a part of you, but they are not you.

Unlike the Calvinists, mindfulness advocates encourage people to notice their thoughts non-judgmentally. They focus more on acceptance and awareness than damnation and rejection. But if this New York Times op-ed is any indication, that guidance sometimes falls on deaf ears (or proves difficult to put into practice). In a piece titled “Actually, Let’s Not Be in the Moment”, Ruth Whippman writes:

I’m making a failed attempt at “mindful dishwashing,” the subject of a how-to article an acquaintance recently shared on Facebook. According to the practice’s thought leaders, in order to maximize our happiness, we should refuse to succumb to domestic autopilot and instead be fully “in” the present moment, engaging completely with every clump of oatmeal and decomposing particle of scrambled egg. Mindfulness is supposed to be a defense against the pressures of modern life, but it’s starting to feel suspiciously like it’s actually adding to them. It’s a special circle of self-improvement hell, striving not just for a Pinterest-worthy home, but a Pinterest-worthy mind.

Sound familiar? At least for some, our mindful moment in history is causing the same anxieties that plagued the Calvinists in the early 20th century. The original principles of mindfulness have been lost in translation, and the practice has been warped by American self-improvement culture. In our more secular times, the enemy is not “sin”, but rather unhappiness or some abstract notion of irrational negativity.

New Thought for the New Age

What happened in the wake of Calvinism’s decline? A movement called New Thought arose to take its place in the early 1900s. Here’s how Einreich describes it:

In the New Thought vision, God was no longer hostile or indifferent; he was a ubiquitous, all-powerful Spirit or Mind, and since “man” was really Spirit too, man was coterminous with God. There was only “One Mind,” infinite and all-encompassing, and inasmuch as humanity was a part of this universal mind, how could there be such a thing as sin? If it existed at all, it was an “error,” as was disease, because if everything was Spirit or Mind or God, everything was actually perfect. The trick, for humans, was to access the boundless power of Spirit and thus exercise control over the physical world.

What we have here is a pendulum swing from hyper-individualism to extreme monism (i.e. everything is the same thing; we are all the universe). The New Thought movement relieved people’s anxieties by zooming out and painting a picture of individuals as part of a larger system, a grander narrative in which they are the audience, the actors, and the theater itself.

Interestingly enough, Ruth Whippman makes the same move in her NYT op-ed, zooming out to talk about broader systemic issues.

It is, of course, easier and cheaper to blame the individual for thinking the wrong thoughts than it is to tackle the thorny causes of his unhappiness. So we give inner-city schoolchildren mindfulness classes rather than engage with education inequality, and instruct exhausted office workers in mindful breathing rather than giving them paid vacation or better health care benefits.

Though her take is less uplifting than the New Thought vision, she’s also attempting to relieve individual anxieties by shifting our focus to the societal whole.

So what should we make of all this? My working theory is that there’s a sort of market for mindfulness that follows a boom-bust cycle. When individualist thought-watching is in high supply, the demand for it decreases. It becomes draining, and cultural critics start to label it as a form of privileged complacency or myopia. People shift their focus to societal discontents—fulfilling latent demand for a more holistic outlook that absolves them of individual responsibility. There will always be attempts at integrating these two world views, but in pop culture the poles are more attractive than the muddy middle.

The mindful meme market

“Beliefs Are Commodities” is a foundational Metaphor We Live By. We often describe belief systems in the language of markets without even realizing it. For example, we buy into beliefs and become really invested in certain ideas. When people betray their beliefs, we say they’ve sold out.

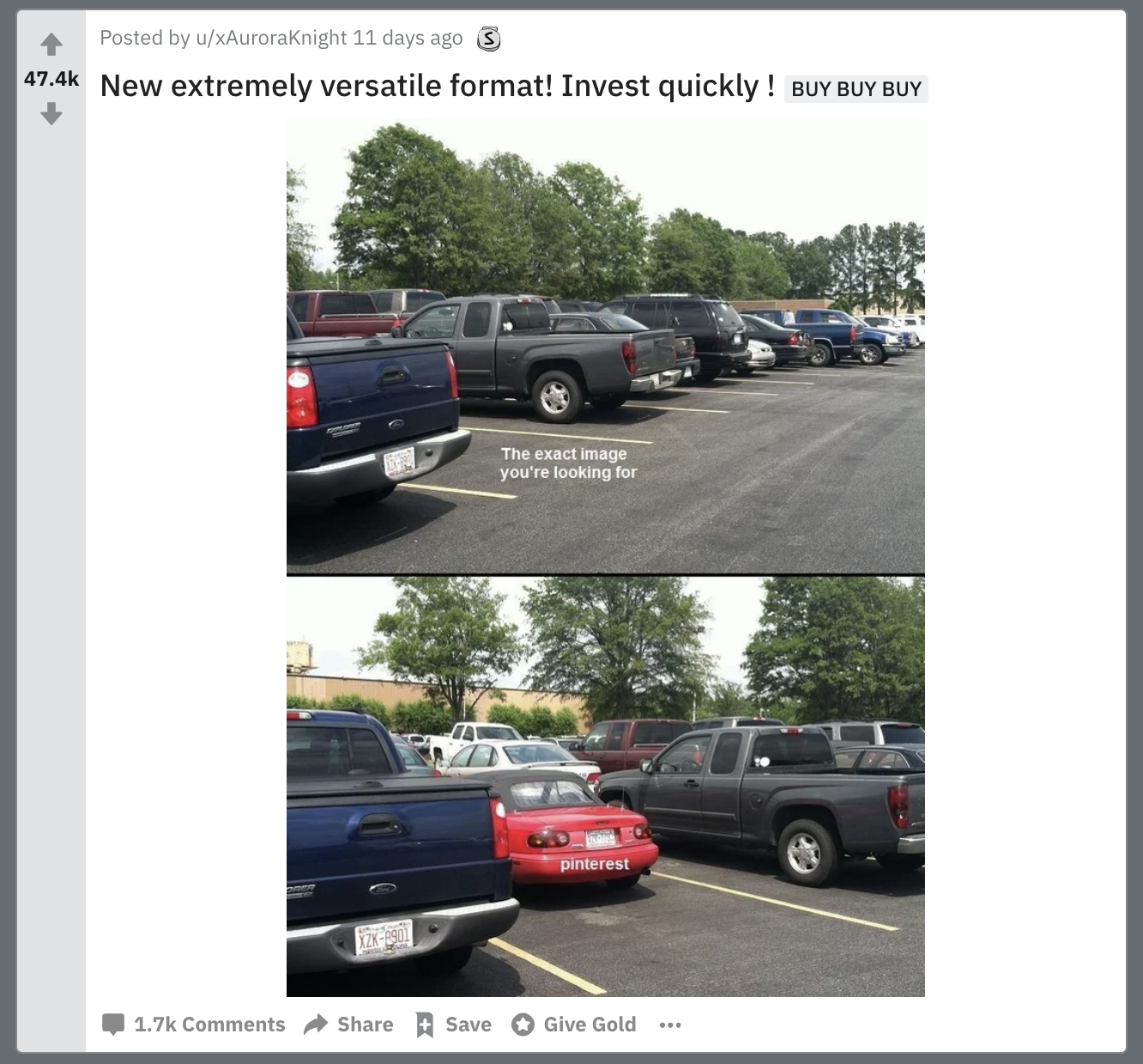

On Reddit, there’s a satirical group called Meme Economy that takes this metaphor to the extreme. Over 750,000 people place fake bets on memes as if they’re capital assets with fluctuating values. Here’s how it works: if a meme is bubbling up online, you say you’re going to buy because you think it has potential to go viral. If you wager that a meme has peaked in cultural relevance, you say sell, sell, sell. (There’s even a fake trading tool called NASDANQ, which lists memes that’ve had a particularly outsized impact). At first glance, it all seems like a big joke for trolls, but I think it actually helps us understand the market for mindfulness.

If we zoom out and think about mindfulness and Calvinism as memes in the broader market for ideas, we see that the same mechanics are at play. To buy is to adopt a belief, to sell is to criticize it and try something else. The boom-bust cycle is driven by aspiring thought leaders (idea investors) who are eager to cash in on new meta-narratives.

When supply of an ideology is high (e.g. mindfulness or Calvinism), so is demand for a contrarian hot take. Critics exploit the inflated price and sell their stake in the idea by publicly signaling disagreement. Price, in this metaphor, is determined by the popularity of a belief and the supposed benefits or harms of adopting it. If enough people pile onto the criticism, they cause the value of the idea to deflate overall. There’s a correction in the ideological market, and the pendulum swings back once again. Back and forth, back and forth. This is what happened in the early 20th century, when the leaders of the New Thought movement began speaking out against Calvinism. And it’s what might happen again in reaction to our current mindfulness fever.

It hopefully goes without saying that this is an oversimplified model, and all models are wrong. I personally don’t buy Ruth Whippman’s notion that mindfulness and political advocacy are mutually exclusive. In many ways, they go hand in hand. (That’s a topic for another day). Unfortunately, nuance does not usually get a lot of traction in the court of public opinion. If we want to figure out how to make mindfulness stick around in this turbulent meme economy of ours, we ought to understand the market dynamics and create a communication strategy that’s more resistant to volatility.