The Eye Roll Test

We love poking fun at jargony clichés. We laugh at people who say they’re finding synergies and streamlining stakeholder alignment. We roll our eyes at social media influencers who post about their Enlightenment quests in Southeast Asia. We dismiss millennials who talk about their quarter-life “crises”. You probably have your own list of buzzwords that you hope you’ll never hear again.

The fridge of human language is filled with words and phrases that have grown moldy. Time tends to suck the meaning out of sentences that were once fresh and alive. Today, this is happening faster than ever. All of the words we use are subject to intense, skeptical scrutiny. I’ve started calling this the Eye Roll Test. A word or phrase fails the ERT when you can’t help but roll your eyes after hearing it. This doesn’t necessarily mean the underlying idea is bad, just that the words it’s “wearing” are out-of-fashion.

But how do once fresh ideas get so stale? Why do some words actually attract meaning over time? How can we protect the ideas we value and stay one step ahead of our era’s eye-rolling cynics?

Failing the test

Let’s take a tour of a few words that no longer pass the ERT:

Synergy. In 1968, Buckminster Fuller used this word with a sense of awe and wonder. He said it’s “the only word in our language meaning behavior of wholes unpredicted by behavior of their parts. Since my experimental interrogation of more than one hundred audiences all around the world has shown that less than one in three hundred university students has ever heard of the word synergy, and since it is the only word that has that meaning, it is obvious that the world has not thought there are any behaviors of whole systems unpredictable by their parts.” Bucky Fuller felt that “synergy” was the best way to describe his then-revolutionary view of the Earth as an interconnected ecosystem. Nowadays, the word is not only overused — it also refers to something far more shallow. It rings hollow.

Philosopher. It’s one of the oldest words in the book. And yet, we’ve become mildly allergic to people who use it to describe themselves. The title doesn’t really pass the Eye Roll Test anymore. We’ve got pundits, public intellectuals, theorists, thought leaders, professors of philosophy — but not philosophers. “Philosopher” feels like a word that’s out-of-time. It doesn’t quite belong in 2019. In his post Rescuing Philosophy, Mike Johnson says, “Part of being a good writer is being in-tune with what words and phrases still have life, and part of being a great writer (like Shakespeare) is minting new ones. My sense is that ‘philosophy’ doesn’t have much sparkle left, and it may be preferable to coin a new word.”

Existential crisis. It’s difficult to imagine someone telling me with a straight face that they’re having an existential crisis. The phrase is played-out, and it usually comes with a joking undertone that tries to dilute its own sincerity. A quick search on Twitter for “existential crisis” yields a barrage of funny memes and people poking fun at their own nihilistic tendencies. I can only assume that existential crises used to be taken seriously. When the term was coined, it mapped onto a dark and intense cocktail of emotions. Today, we have words like depression and anxiety, but they don’t cut quite as deep. There’s a gap — we might call it a linguistic lock-in — between our felt sense, the words we have available to us, and the way those words are understood by our listeners.

Meaning magnets

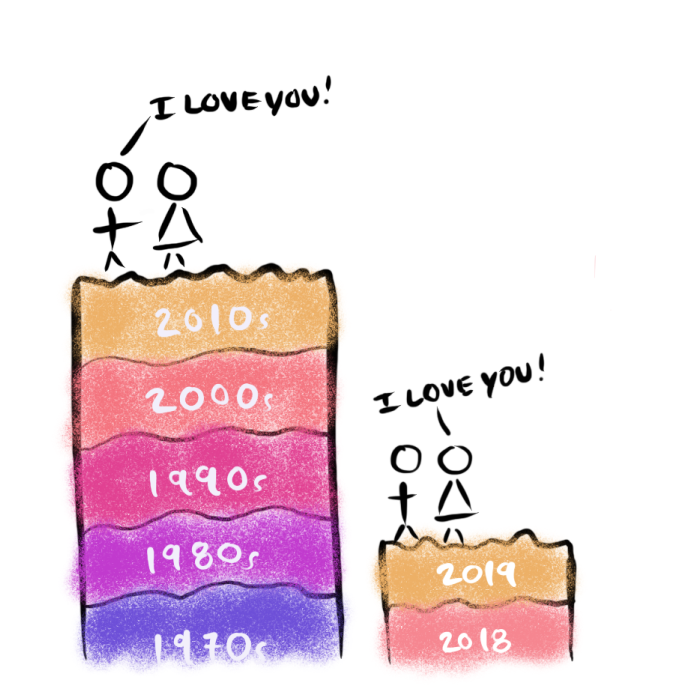

Not all language goes stale. As Chris Beiser pointed out to me on Twitter, some phrases act more like magnets that “attract” meaning. The phrase “I love you”, for example, tends to grow deeper with time. Meaning flows towards it. For older couples, it calls to mind an entire lifetime of shared experiences.

Here’s how Chris explains the difference between words that attract meaning over time and words that get stale.

When your use of a word/phrase coincides with a strong emotion, it tends to bulge with meaning over time. Each time you use it, you’re associating it with a moment that feels really intense on the inside. (Bonus points when you say the phrase while you’re sharing an emotional reality with someone else). For example, “I love you” is usually accompanied by a pretty powerful concoction of feelings.

When your use of a word/phrase doesn’t go with a strong emotional state, it’ll gradually lose its meaning over time. It becomes, as we say, a bunch of hot air. Phrases that lose their meaning over time are usually abstract intellectualizations. They’re used retroactively — as placeholders that signify (but can’t induce) intense emotions. For Buckminster Fuller, the word “synergy” was not just a theoretical construct. It called to his mind a beautiful, vibrant sense of Earth’s ecosystem and our place in it. Over time, the connection between the word and his felt sense of it became dissociated, divorced. Nowadays, the letters are still there, but they don’t pass the Eye Roll Test. I love Scott Preston’s description of this phenomenon:

An older language is devalued because its terms no longer represent our true experience. We call older, previously dignified names and words passé. We dismiss them from service as having become mere meaningless formula, cliché, or cant — zombie words from which the life (meaning) has fled while their corpses linger around like hungry ghosts and lost causes. We call “lip-service” the speaking of formerly grand names and words from which the life (which is the meaningfulness) has long since departed because they no longer adequately symbolize our true experience. In times of very great change, words and names fall out of usage like dead leaves from a tree in late autumn.

This explains why, in some cases, even the phrase “I love you” can get stale over time. If its utterance doesn’t coincide with a strong shared emotion, it eventually gets hollowed out.

Time traveling translators

So, how to prevent important ideas from failing the merciless Eye Roll Test? The test is a moving target, always shapeshifting and adapting to the norms of mainstream culture.

There’s a difference between protecting ideas and preserving them. Protection is not as passive as mere preservation. It’s a generative, creative process. Preservation is what happens in museums — those sterile graveyards of culture where we place ideas in glass-case coffins and leave them there to rot in public view.

The Declaration of Independence on display.

The Declaration of Independence on display.

Every generation has to resurrect dead language with mediums that feel relevant, of-the-moment, and even a little weird. We have to dress up the ideas we value in “costumes” that are fit for the times. For reference: Bill Wurtz is doing this with his irreverent cartoon videos about geopolitical history; ContraPoints is doing this with her slightly creepy Drag-Queen-meets-Philosopher-King videos. Text won’t be the primary technology of transmission for kids in the future. Meme-ducation is here, and it’s going to get funky.

I care about this deeply because I think the bus ride from boring language to widespread political apathy is surprisingly short. When our political ideas start sounding stale, people opt out of civic engagement. Their eyes glaze over as they listen to politicians who sound like robot zombies, paying lip-service to the ghosts of revolutionary ideas. The end state of this linguistic degeneration is not pretty.

Remember that every phrase you roll your eyes at today was once alive and full of meaning. Try to investigate why people once resonated with it. And once you have a working theory, test it out by translating the phrase into 2019-speak. In the internet age, words and phrases get stale faster than ever. We’re caught in a cat-and-mouse game, stuck on a treadmill that won’t turn off, trying to refurbish our ideas and hoping they’ll pass the Eye Roll Test.

This game is happening all around us now:

That we are really dealing with a conflict of times, and not geo-political spaces … is indicated by the propensity these days to preface all older terms with the prefix “neo-”. We have neo-conservatism, neo-liberalism, neo-Marxism, neo-socialism, and even neo-fascism. These are indications of identities … attempting to retain old relevancy, legitimacy, and identity in the face of the new era presently in formation … Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy has used the term “polychrone” to describe the condition of human society in the global era — many times, histories, traditions or generations co-existing.

Loss of meaning is a side effect of information overload. Sprayed by a firehose of ideas and speech, we quickly grow tired of what we’ve already heard before. (Things are changing so fast that it sometimes even feels necessary to translate 2009-speak into 2019-speak). If we want to keep our language and our politics feeling dynamic, we have to become good intertemporal translators — linguistic time travelers, continuously reanimating the corpses of yesteryear’s ideas.

This post is inspired by Jared Janes' Twitter thread + conversations with Josh Morin, Visakan Veerasamy, Chris Beiser, and Scott Preston. If it sparked some thoughts in you, click here to share them. Let’s get a conversation going.