You can handle the post-truth: a pocket guide to the surreal internet

The future is already here, it’s just not universally understood. I know I’m not alone when I say that I can feel the gap between my world and my parents’ world widening. They barely know what memes and influencers are — and yet, our culture is being completely re-shaped by them. Making sense of 2019 feels like a part-time job. What’s real, what’s fake? It’s hard to keep up.

Thankfully, groups like Theorizing the Web and RadicalxChange are helping us piece together the puzzle of our present. I attended both of their conferences last month and was blown away by what I learned.

Theorizing the Web is a weird and wonderful gathering where academics and technologists share their theories about wtf is happening online. The conference was started 9 years ago by a small group of tech-savvy cultural observers who wanted to take the internet seriously as an instigator of large-scale sociological change. (Back when Zuckerberg stayed far away from Congress and techno-optimists were praising Twitter for creating the Arab Spring). RadicalxChange is new on the scene — an eclectic mix of economists, policy wonks, activists, crypto nerds, and artists who are trying to think more creatively about how to improve our social institutions. Together, RadicalxChange + Theorizing the Web painted a surreal picture of how bad actors are creating weapons of information warfare to re-shape our world. I want to pass on my notes before they get too out of date.

Sections

- The "souls" of virtual folk

- Roll-your-own reality

- Digital rebirth & the death of consensus

- The only way out is through

The "souls" of virtual folk

In 2016, a digital marketing agency called Brud created a computer-generated Instagram influencer named Lil Miquela. She’s a “biracial” “woman” who makes music, sells product, and seems to hang out in real-life places with real-life celebrities. She represents the culmination of a decades-long project to make brands more personal and relatable, the evolution of the corporation from Big Other to girl next door.

Judging by the comments on her pictures, many fans don’t even realize she’s not “real.” Her creators seem to enjoy stoking confusion about what’s real vs. fake, and the folks at Instagram are making it easy for them to do that. They gave Lil Miquela a verified blue checkmark, which normally only goes to public figures. In our age of “am-I-interacting-with-a-Russian-bot-or-not”, these checkmarks are digital arbiters of reality. But the line between fact and fiction is getting increasingly blurry.

Last week, Calvin Klein triggered an outrage cycle after sharing a music video in which Lil Miquela kisses Bella Hadid. It's a classic example of the toxoplasma of rage principle: the more controversial something is, the more it gets talked about. One day, we'll learn to see through this sort of corporate emotional manipulation.

Lil Miquela gained over a million followers and spawned a whole crew of CGI influencers, some weirder than others. There’s Shudu, a very black CGI model created by a very white photographer. And KFC recently unveiled a sexy CGI version of Colonel Sanders.

But what’s strange about Lil Miquela in particular is that she’s “woke.” She writes ironically detached posts about how her creators are using her to sell consumer goods. She talks about why she dislikes capitalism and what it’s like to be multi-racial. In other words, the agency behind Lil Miquela co-opts the language of political activists in order to make her “relatable” and sell more products. We’ve seen this happen before. After the counter-cultural movement of the ‘70s, for example, marketers latched onto “sexual liberation” and “individual expression”. Sex became highly commodified and consumption became a primary method of self-expression. Pac-man PR feeds on the language of its ghost attackers.

Colonel Sanders, the first of what's sure to be many CGI brand influencers.

Lil Miquela got me thinking about the difference between her account and a politician’s. I’d go so far as to say that most politicians' social media accounts feel more fake than Lil Miquela’s. Politicians pose as “people” on social media even though there’s usually a team managing their online presence. There are some exceptions, of course. Trump and AOC are striking a chord because there doesn’t seem to be much middle management between their minds and their tweets. It’s only a matter of time before someone tries running a CGI candidate for office. With enough deepfake videos and a good social media strategy, it would probably take a while to get exposed as not “real”. And even then, our hypothetical candidate could claim that the “real” politicians aren’t “real” either.

Inauthenticity is becoming the hallmark of our era: faked Facebook data, faked college admissions applications, faked resumes and “bullshit jobs”, faked news, faked mortgage-back security ratings, AI pretending to be humans, humans pretending to be AI. Lil Miquela and her CGI crew will expose the “inauthenticity” of our corporations and public figures, which will of course challenge our notion of authenticity altogether. Authenticity itself is a relatively new way of thinking about identity and human behavior. I trust we’ll create a new mode of understanding that’s better fit for the surreality we live in — one that demands transparency and acknowledges that people are beginning to see through all the manipulative corporate PR.

Lil Miquela is a fairly benign example of how big business is co-opting the language of would-be critics. For a more alarming case study, we should look at what’s happening in Brazil’s ongoing information war. Last year, Rafaela Nakano spent several months researching a nation-wide truck drivers' strike that was organized and managed through WhatsApp. She discovered that far-right business leaders managed to infiltrate these WhatsApp groups. Once inside, they started making propaganda videos that spread like wildfire. They destroyed the strike’s momentum by offering false promises, sowing confusion, re-directing the narrative to serve their interests, and making it difficult to separate fact from fiction. Like a virus, they infected the host cell and started controlling it from the inside. If we’re not careful, a hyper-realistic, hyper-charismatic CGI influencer could be used to automate this kind of disinformation campaign in the future.

Brazilian oligarchs are borrowing from the playbook of Russia’s Internet Research Agency (IRA), which has developed fine-tuned techniques for spreading confusion and misinformation online. Renee DiResta, a researcher at Mozilla, explains that online conversations are ripe for manipulation because they take place on an infrastructure that’s built for advertising. This infrastructure has three main components: audience consolidation, personalized targeting, and game-able algorithms. It’s a particularly powerful combo for those who wish to sow discord.

Since 2014, the IRA has employed thousands of white collar workers who study online communities in order to imitate them, form personal relationships with internet activists, and organize IRL protests. What they’re doing amounts to a sort of digital appropriation or group identity theft. They stoke people’s ingroup identities with propaganda and impressively nuanced memes. To an untrained eye, they seem “authentic.” What feels most perverted is that they’re turning our deepest causes and convictions into weapons that can be used against us. The IRA’s Black Lives Matter group was one of the largest on Instagram, and it was just one of hundreds of targeted messaging campaigns tailor-made for specific subcultures across the political spectrum. Last year, the DOJ released a report that documents the activities and strategies of the Internet Research Agency in excruciating detail. But the IRA doesn’t really care if its tactics are exposed. They don’t have an ideological agenda beyond chaos and confusion — the more doubt, the merrier.

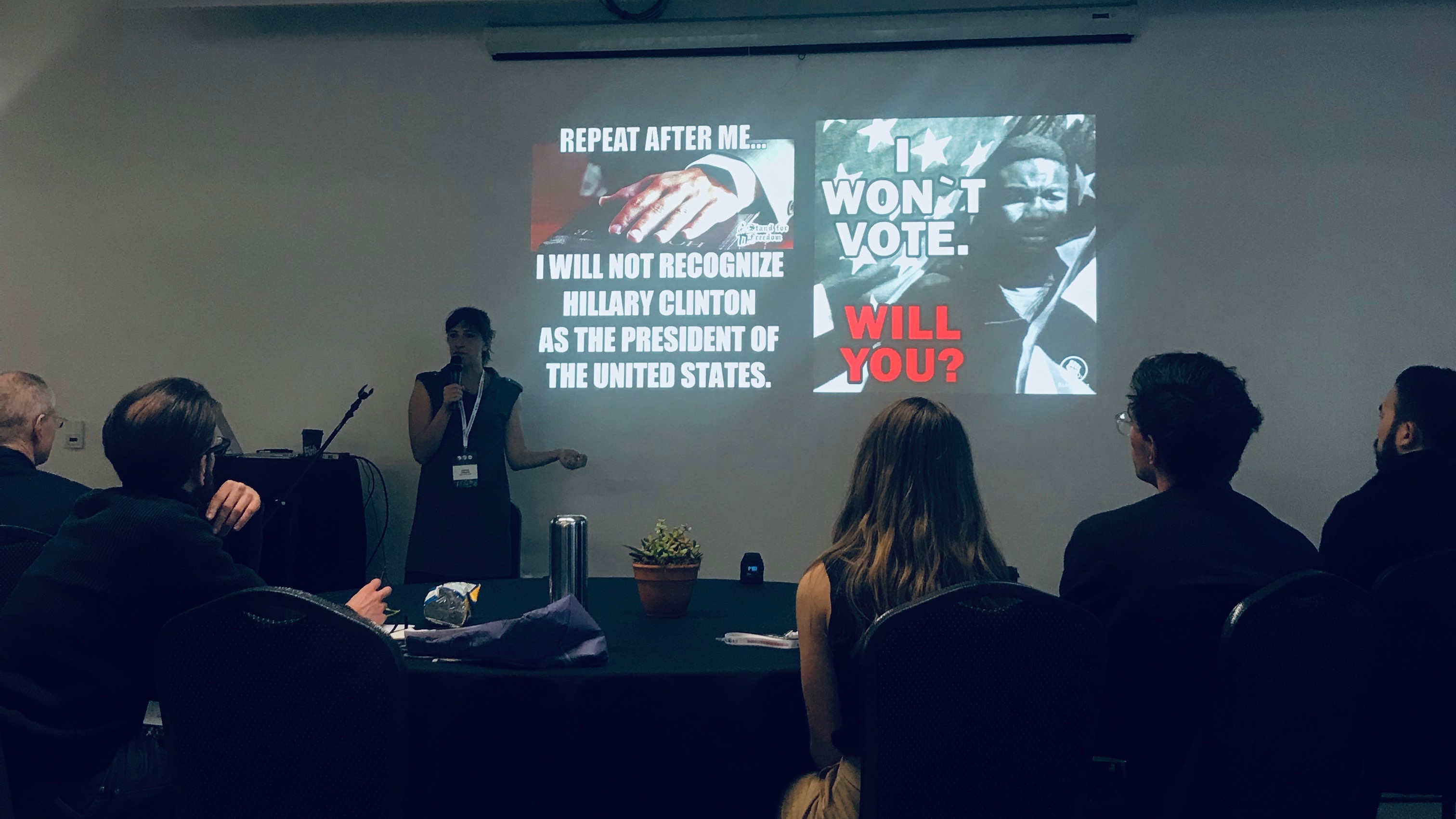

Renee DiResta at the RadicalxChange conference, presenting some of the IRA memes she uncovered in her research. They were shared widely within targeted communities.

So far, we’ve covered how marketing agencies and foreign entities are blurring the line between what’s real and what’s fake. This development is quite confusing on its own. But they’re not alone — the internet has democratized the ability to create new reality bubbles and distort old ones. We’re just beginning to grapple with the consequences of this seismic cultural shift.

Roll your own reality

Over the last few years, we’ve witnessed a resurgence of conspiracy theorizing thanks to people like Alex Jones, Roger Stone, and a small army of YouTube stars you’ve probably never heard of. In response, the Left has organized marches for science in which huge crowds of people chant “I believe in Science!” Meanwhile, there’s an ongoing replication crisis in psychology, a growing problem of misaligned incentives in academic peer review, and a slowdown of “progress” in science. This makes for a very weird cultural cocktail, indeed.

Sun-ha Hong argues that the Left has created a straw-man caricature of far-right conspiracy theorists. They chant “I believe in Science” because they’re convinced the other side doesn’t. But they’re mistaken. Listen closely to the new conspiracy theorists, and you’ll learn that they very much perceive themselves to be part of the Enlightenment tradition. They say they believe in the principles of science, of creating hypotheses, of testing them, of experimenting, of independent thinking. Both the “I believe in Science” Left and the conspiracy theorizing Right claim to be heirs of the Enlightenment. What’s different about the far-right is that they stopped trusting institutions and took matters into their own hands. This approach feels less patronizing and more empowering than listening to experts who seem so distant and out of touch. In a sense, the media literacy movement backfired.

A protester at the March for Science in D.C.

As science becomes increasingly specialized, people outside of academia feel they have no choice but to appeal to authority and evangelize their “belief” in it. The success of Enlightenment rationality eventually led to its inaccessibility. In a weird twist, the only laypeople I’ve seen doing experiments are the conspiracy theorists featured in Netflix’s documentary about Flat Earthers.

Except in extreme cases, it’s important not to distance these people or publicly shame them. Distancing leads to further social isolation, which can lead to further radicalization. We have to soberly investigate how they spiraled into their current belief system, acknowledge the kernel(s) of truth inside their theory, separate the ideas from the people who hold them, and understand that good people can be hosts to bad memes. The harder you push back, the more they dig in. It’s one of those counter-intuitive things like turning the steering wheel into the turn when you feel your car spinning out. (ContraPoints' YouTube video on the incel community is one example of how to do this tactfully and creatively).

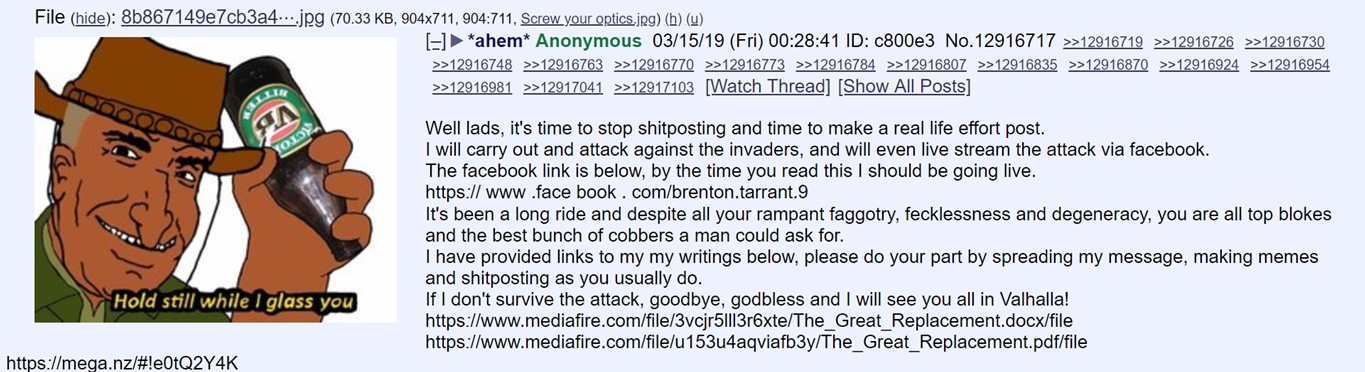

Sadly, more and more cases of online radicalization are morphing into offline violence. In 2016, a homegrown terrorist fired shots at a Pizza restaurant in D.C. after reading a conspiracy theory that claimed Hillary Clinton was running a child sex ring in the basement. This year, there have already been two cases of 8chan-inspired mass shootings at houses of worship. The New York Times described the recent chain of IRL violence as a “sticky meme.”

The Christchurch shooter announced his intentions on 8chan before carrying out the tragic attack. Credit: bellingcat

Let’s be clear: online radicalization is fueling a new wave of terrorism at home and abroad.

We need to take a hard and sweeping look at how people are becoming radicalized online. By now, most internet people are pretty familiar with the sensationalist cycle of YouTube’s recommendation engine. An innocuous search can lead viewers to radical content because YouTube optimizes for viewing time and sensational content is more engaging.

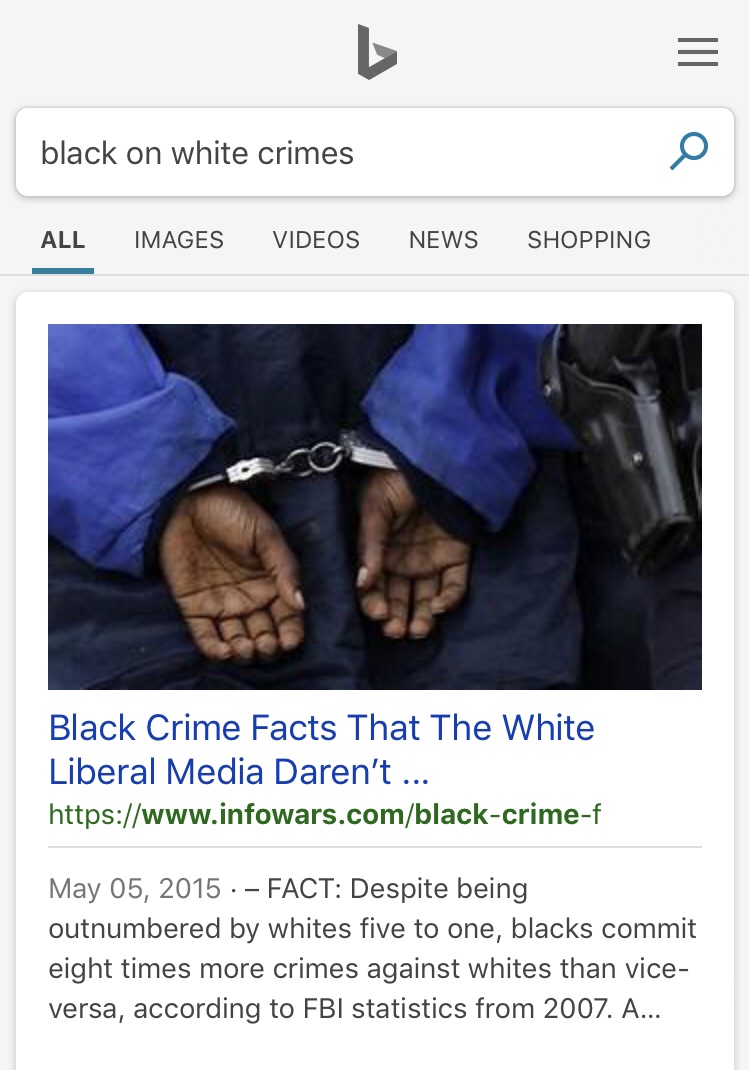

But there’s also a darker “conversion funnel” for bad memes. danah boyd calls them data voids. Here’s how they work: savvy online extremists are taking advantage of obscure search terms that have little to no content associated with them (hence the term “void”). They create articles using these terms and encourage people to search for them, knowing that only one point-of-view will be represented on the results page. These data voids become memetic traps that suck people down a radical rabbit hole. Here’s an example from the Data & Society report on data voids:

Few people ever searched for “Sutherland Springs” until November 4, 2017, when news started coming out that a shooter walked into a Baptist church and began shooting. As news rippled out, people turned to search engines to understand what was happening … Adversarial actors, intent on capitalizing on what would be a sudden interest in a breaking news story, decided to take advantage of this opportunity. They turned to Twitter and Reddit in an effort to associate both the town, and shortly after, the name of the shooter with the term “Antifa” … Their goal in creating this association was to provide a frame that journalists would have to waste time investigating (to eventually debunk). Furthermore, they wanted early searchers to believe that this shooter’s motives were part of a leftist conspiracy to hurt people. In short order, these adversarial actors managed to influence the front page of search queries, inject “Antifa” into auto-suggest, and trigger journalists to ask whether Antifa was involved. In a matter of hours, Newsweek ran the headline “Antifa' Resonsible for Sutherland Springs Murders, According to Far-Right Media.” This influenced the news content, which search engines take more seriously, and increased the visibility of this association.

I tried this out for myself by searching “black on white crimes” on Bing. The very first result comes from Alex Jones' Infowars site because this phrase is generally not used in mainstream media — it’s a data void.

What’s to be done? I think our options are to go local, go authoritarian, go virtual, or go meta.

Going local

Going local is a potential antidote to conspiratorial spiraling. If you have a “conspiracy theory” about how your neighborhood is being run, you can usually investigate for yourself, become a community organizer, and change things. Conspiracy theories co-arise with large power imbalances. People become conspiracy theorists when they feel powerless in the face of large, abstract systems.

If we can’t trust what we’re seeing in mass media, maybe we’ll return to thinking about the things we can do something about in our communities. Maybe we’ll shift the locus of our identity from national parties to local relationships. I’m already starting to see a renewed interest in community building among a small but growing group of people who are creating “crews” in the “empty space between the self and the crowd.” A few examples: The How We Gather project at Harvard Divinity School, which is documenting millennial groups like Soul Cycle and CrossFit through a religious lens. The Microsolidarity Proposal, which put together some concrete ideas for how to build communities in the internet era. Joe Edelman’s future togetherness test kitchen, which is prototyping “weird new ways for community to form and for people to support one another.”

And in the 21st century, “local” doesn’t necessarily have to mean “geographically proximate”. It can also refer to virtual spaces with internet friends who share your interests and passions, but live halfway across the globe. We’ll probably see more of this “digital localism” as Facebook and Google shift their focus to private communications.

Zuckerberg describing Facebook's strategy at this year's F8 conference. Credit: Amy Osborne

Going authoritarian

Authoritarianism controls the flow of information so that conspiracy theories never spread in the first place. Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube have tried to moderate content on their platforms, but this has proved to be an extremely thorny game of whack-a-mole and a textbook example of a wicked problem. Countries like China, North Korea, and Iran have cracked down on the open internet. They’re trying to create cultural cohesion by shielding their citizens from subversive content.

Going virtual

Going virtual means dropping out of the messiness of mainstream society and deciding to play a new, more constrained game with simpler rules. It seems like a way to disengage from questions about “what’s real” and focus instead on a virtual world of your choice — be it Fortnite, World of Warcraft, or something else. At least, that’s how it’s sold. There’s a sense of certainty, control, and comfort that comes with escaping to a fantasy world that you know is all made up. We’re seeing signs of this trend already: Andrew Kortina and Namrata Patel argue that “the drop in labor participation rate of young men is a result of the increase in the availability and quality of media entertainment leisure.” In other words, they’d rather participate in Fortnite’s economy than the one out here in the “real” world.

The tag line of Occulus' new marketing campaign: "Define your own reality."

Going meta

Meta is a disposition that encourages people to seek competing narratives rather than dogmatically believing any one theory. More on this later.

For a concrete example of what going meta looks like in practice, let’s look at Epsilon Theory’s narrative structure project. They’re using natural language processing to analyze the entire journalism industry as an organism, and then reporting on that thing’s behavior. Their goal is to “make you a better, more informed consumer of political news by showing you indicators that the news you are reading may be affected by (1) adherence to narratives and other abstractions, (2) the association/conflation of topics and (3) the presence of opinions.” They want to “cut through the intentional or unintentional ways in which media outlets guide you how to think about various issues.”

Epsilon Theory's narrative map of 2020 election stories. If many different media outlets are using the same talking points, there's reason to read with skepticism.

Epsilon Theory’s approach is an example of what Peter Limberg calls playing the meta-game. They’re tracking the emergent behavior of all the individual stories and making the growing hivemind a little more transparent. Epsilon Theory is focused mainly on political and financial narratives, but we’ll probably see something like it in every industry.

Digital rebirth & the death of consensus

As if living online weren’t crazy enough, people are also thinking creatively about how to die online. In the coming years, the amount of dead people on Facebook will exceed the size of some small nations. But not everyone thinks about dying online in the same way. Timothy Recuber describes three different philosophies:

Some people think of internet death as a digital memorial. This is the metaphor that Facebook uses when they memorialize the profile of someone who recently passed away. Friends and family can continue to post messages on their loved one’s wall. This isn’t a far cry from the memorial services we participate in IRL. They help people grieve and move forward.

Others think of internet death as an heirloom or artifact. This is about preserving the things someone created while they were still alive, much like pre-digital artwork and books. Aaron Swartz, for example, left an incredible archive on his blog which has inspired many people (including myself) in the years after his death.

But here’s where things get surreal: people are starting to think of internet death as a sort of digital reincarnation. They imagine themselves becoming ghost-like after they pass on. Several companies are trying to develop AI chatbots that allow people to talk with the dead. These bots are trained on a corpus of the deceased person’s communication history — emails, text messages, social media posts, etc. In the future, AI chatbots could merge with hyper-realistic VR avatars to create believable simulations of people that stick around after their physical death. Facebook and a small company called ObEN already announced earlier this year that they’re able to create high-fidelity avatars of people’s bodies for use in VR (which they call “personal AI for all”). “Your appearance can be used for generations,” says the creator of Shudu, the first digital supermodel. “Imagine what will happen if Kim K. gets a 3D double made. Will it ever end?”

Whereas memorial pages and heirlooms are static, these chatbots and VR avatars are deeply interactive. They represent a potential phase-shift in the way we die online by allowing our ancestors to continue communicating with us after we’re gone. Like deepfakes and CGI influencers, they’re blurring lines that we used to take for granted and confusing what once seemed like a solid dichotomy: life vs. death. By promising us the appearance of immortality, they’re turning our digital selves into quasi-gods.

But if we zoom out far enough, it becomes clear that this isn’t a totally new phenomenon. Media technology has always been used to commune with the dead. For much of pre-modern history, religious institutions wielded this power. They led the way in creating new types of media tech so that the teachings of their prophets might transcend death. For example, the Catholic Church funded illuminated manuscripts, awe-inspiring architecture, stained glass murals (the original back-lit screen!), and realistic painting techniques like those of Michelangelo and Raphael. By encoding Jesus’ ideas in architecture, music, writing, and art, the Church made it possible for believers to continue communicating with him more than 2,000 years after his death.

There’s no reason to think that traditional religious institutions won’t continue to embrace new media in the digital era. They're already experimenting with VR worship services and cyber baptisms (pictured above). We're also witnessing the birth of techno-shamanism — a mashup of new tech and ancient wisdom traditions.

What’s different about the post-truth present is that religious institutions have lost their monopoly on media tech and “immortality”. Soon, says Venkatesh Rao, “any ordinary human with sufficient imagination will have the kind of cultural superpowers that was once limited to the high priests and Pharaohs.” We’re now living through a gold rush for social capital accumulation: media influencers and extremists alike are competing with traditional religions to pull as many people as possible into their filter bubbles. And we’re becoming god-like in our ability to shape people’s realities. These alternate conceptions of reality are coming into conflict with one another, which is why 2019 feels so surreal. Never before have we had to deal with so many competing versions of the truth.

All of these reality bubbles tell different stories about the past and paint vastly different visions for the future. They’re making us more fragmented than ever before in an age that requires more coordination than ever before. So, how can we move through and beyond these deep divisions?

The only way out is through

The fragmentation of reality means that our current method of understanding history (i.e. a single narrative sweep from the “beginning” to the present) is no longer adequate. Consensus history as we knew it in the 20th century will likely be difficult, if not impossible, to recreate. How could we possibly compress all of these contradictory reality bubbles into a single history textbook? The cat’s out of the bag — school kids have access to a dizzying array of alt histories at their YouTube-loving fingertips.

If we want a shot at bridging these divides, I think our understanding of history will have to go meta. In fact, this has already begun to happen in academia and in new media. To go meta is to study the way history has been (and is) written. It’s trying to understand the story of the stories we’ve told about ourselves. There’s no one narrative that rules them all, no one way to connect the dots from the past to the present. The “meta” stance inspires humble curiosity and peace-of-mind amidst the many versions of reality we face in 2019.

Right now, it’s difficult to feel inspired by the stories we tell about ourselves. Most of our narratives are quite dystopian, and we’re surrounded by a bunch of escape artists: interplanetary escapists (Musk and Bezos), apocalypse escapists (doomsday preppers and bunker buyers), drug-fueled escapists (via opioids and psychedelics), death escapists (cryonics and anti-aging research), biology escapists (transhumanists and wannabe cyborgs), mainstream news escapists (the man profiled in NYT who fled to a cabin in the woods after the 2016 election).

We need to engage rather than escape. Yes, things on the internet are confusing and chaotic and weird right now. That’s because the goal of the bad actors we’ve covered is to deliberately manufacture confusion and make you feel apathetic about what’s real vs. what’s fake. My hope is that exposing some of these techniques makes them a little less mysterious and a little less surreal. You can handle the post-truth. Because you can learn the truth about how these so-called “post-truth” movements work.

I think this sort of awareness will create new ways of relating to what’s happening online. Maybe we’ll start to see through corporate emotional manipulation carried out by entities like Lil Miquela. We’ll understand the ways in which extremists like the IRA capitalize on our outrage, and we’ll develop strong immune systems to their attacks. We’ll cultivate a sense of compassion when we begin to understand how good people get sucked into data voids and drawn in by bad memes. Like Epsilon Theory, we’ll start to see the whole ecosystem of narratives instead of just individual articles. We’ll become miniature meta-historians — less dogmatic about our personal narratives and more capable of holding the multitudes contained in our histories. And we’ll begin to reconnect offline by transforming our inspiring internet communities into IRL friendships and collaborations.

We’re not just post-truth, we’re pre- something else that’s yet to be determined. “Post-” is just what you call a transitional era while you’re trying to figure out what the hell is going on. It’s never the end of history. We’re going to grow whatever’s next out of this messy, surreal soil.

*For more on this topic, check out the Are.na channel where I’m collecting reference materials: “A post-secular age”. If you have comments or questions about this post, please drop htem here.

This post is inspired by the work of: Renee DiResta, Jared Newman, Peter Limberg, Venkatesh Rao, Sun-ha Hong, Maggie MacDonald, Joe Edelman, Anna Gat, David Chapman, Ben Hunt, Eugeine Wei, ContraPoints, danah boyd, Timothy Recuber, Toby Shorin, Juniper M, Robert Evans, Dina Lamdany, Micah Redding, and Scott Alexander.