Metaphors we believe by

It’s 2013, and I’m lounging on the hardwood floor of my childhood bedroom with a blasphemous book that I smuggled home from college: Sam Harris' Letter to a Christian Nation. I devour the whole thing in a single sitting. It feels like Harris is letting me in on a giant secret, a Big Truth that my very Christian upbringing had kept hidden from me. God is dead, he says. We killed him a few hundred years ago and replaced him with a sophisticated scientific understanding of life, the universe, and everything.

Fast-forward six years, and I’ve started to realize that the God vs. science situation is a bit more complicated than Sam Harris led me to believe. The more I learn, the more I suspect that rationalists only managed to kill a very narrow and anthropomorphic conception of God. People who study complex systems started using new words to talk about god-like phenomena — metaphors that are more palatable to secular minds. I believe these new words can help scientifically-minded people better understand what it actually felt like to believe in God before science became a Thing. Let’s take a tour through the pantheon of 2019 and explore what these seven “gods” might teach us in our era of ecological crisis and post-truth confusion.

Human Colossus

The god of collective human knowledge

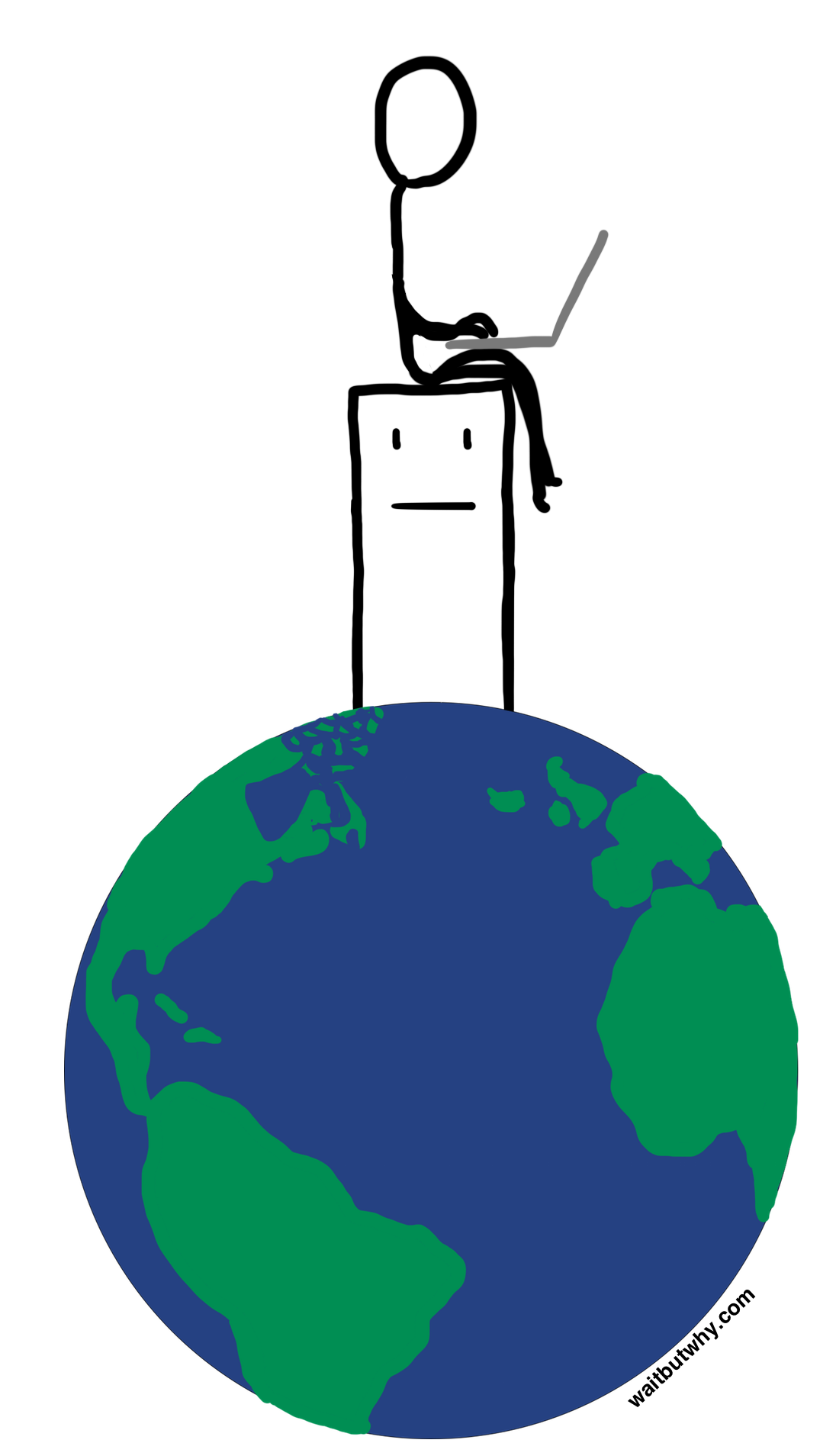

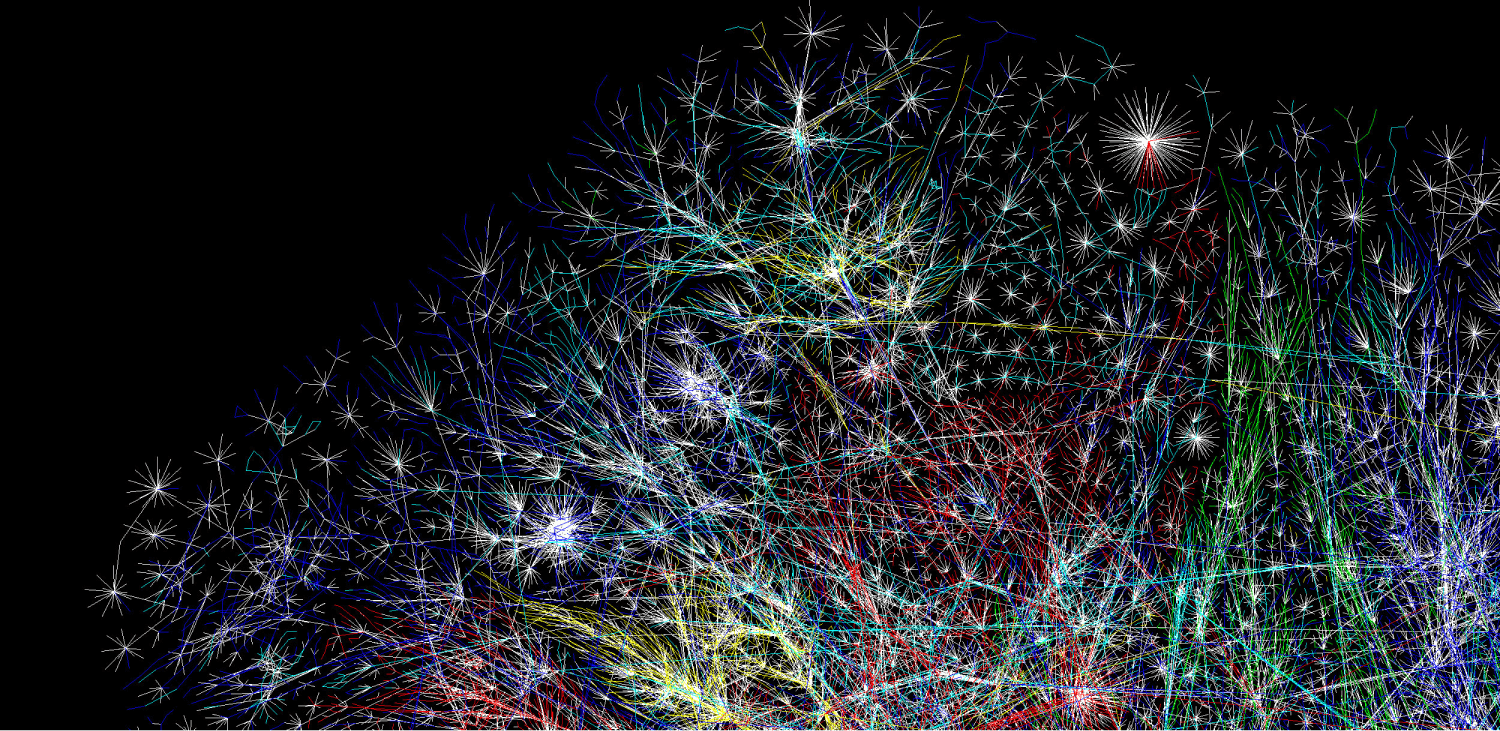

First up in our tour of the 2019 pantheon: the Human Colossus. This god was named by the blog Wait But Why, and it helps us imagine all 8 billion humans as a single super-organism. It’s inspired by the Colossus of Rhodes — an ancient Greek statue of the sun-god Helios. Standing 108 ft. tall, the statue was built to celebrate a victory in battle and later served as a model for the French designers of the Statue of Liberty. Wait But Why re-imagines the Colossus as a giant person sitting on top of a giant computer. Each one of us is like a little cell in this “body” that we can’t quite see from the outside.

In the past, humans lived in small isolated tribes that were spread out all across the planet. Traders and explorers often journeyed to faraway lands, but cultural cross-pollination was limited by the speed of their transportation technology. We’ve spent the last few hundred years building communication infrastructure that connects billions of people together: ships, trains, telegraphs, phones, radio, television, internet. Now we live in a globalized economy where instantaneous information transfer is the new normal. We’ve summoned the Human Colossus with our reverence for media tech, financial profits, and knowledge accumulation, and it’s growing faster every year. Here’s how Tim Urban explains this colossal phenomenon:

The better we could communicate on a mass scale, the more our species began to function like a single organism, with humanity’s collective knowledge tower as its brain and each individual human brain like a nerve or muscle fiber in its body … The Human Colossus began inventing things that no human could have dreamed of inventing on their own — things that would have seemed like absurd science fiction to people only a few generations before. If an individual’s core motivation is to pass its genes on, which keeps the species going, the forces of macroeconomics make the Human Colossus’s core motivation to create value, which means it tends to want to invent newer and better technology. Every time it does that, it becomes an even better inventor, which means it can invent new stuff faster.

To paraphrase Mark Zuckerberg, this god is a product of our long-running effort to make the world “more open and connected.” The Human Colossus has brought us many amazing innovations with its sprawling server farms and network infrastructure. It’s also brought us to the brink of ecological collapse by exploiting Earth’s natural resources. TBD whether we will regret calling it into existence.

Twenty-four hours of global Twitter activity. Source: New England Complex Systems Institute. According to Mary Meeker, over half of humanity is now connected by the internet.

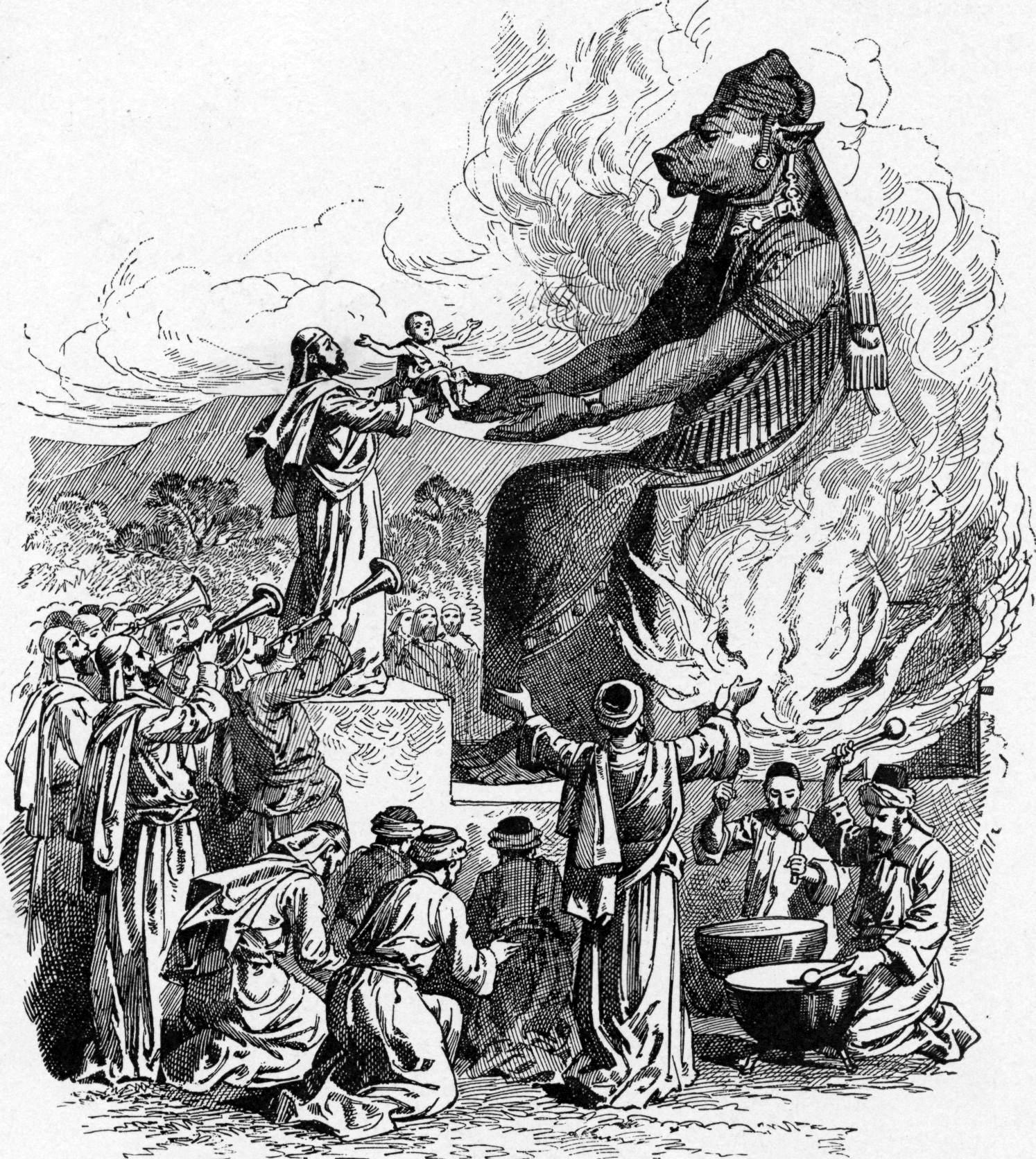

Moloch

The god of coordination failure

Our next god is more like a demon. Moloch was originally a Biblical bull-like deity who demanded very costly sacrifices from his followers. He’s appeared in religious texts and English literature throughout the ages, including John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667) and Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” (1955). Most recently, he was brought back to life by the blog Slate Star Codex. In an internet-famous essay called Meditations on Moloch, SSC warns us that this god is behind humans' failure to coordinate at scale. He points to a wide variety of intractable problems — climate change, the prisoner’s dilemma, overfishing, arms races, government corruption — and explains the underlying pattern they all have in common:

The implicit question is: if everyone hates the current system, who perpetuates it? And Ginsberg answers: “Moloch”. It’s powerful not because it’s correct — nobody literally thinks an ancient Carthaginian demon causes everything — but because thinking of the system as an agent throws into relief the degree to which the system isn’t an agent … In some competition optimizing for X, the opportunity arises to throw some other value under the bus for improved X. Those who take it prosper. Those who don’t take it die out. Eventually, everyone’s relative status is about the same as before, but everyone’s absolute status is worse than before. The process continues until all other values that can be traded off have been — in other words, until human ingenuity cannot possibly figure out how to make things any worse.

What’s particularly scary about Moloch is that he forces humans into coordination problems against their will. In a nuclear arms race, for example, most people would prefer that no one has nuclear weapons. But each nation is compelled to develop them if they want to hold onto their power. We can’t control Moloch because Moloch controls us. He’s widely feared by rationalist circles on the internet, and he motivates many blockchain fanatics to create new technologies for improving human coordination. Techno-optimists who worship The Human Colossus sometimes believe that they’ll be able to tame Moloch. But others aren’t so sure.

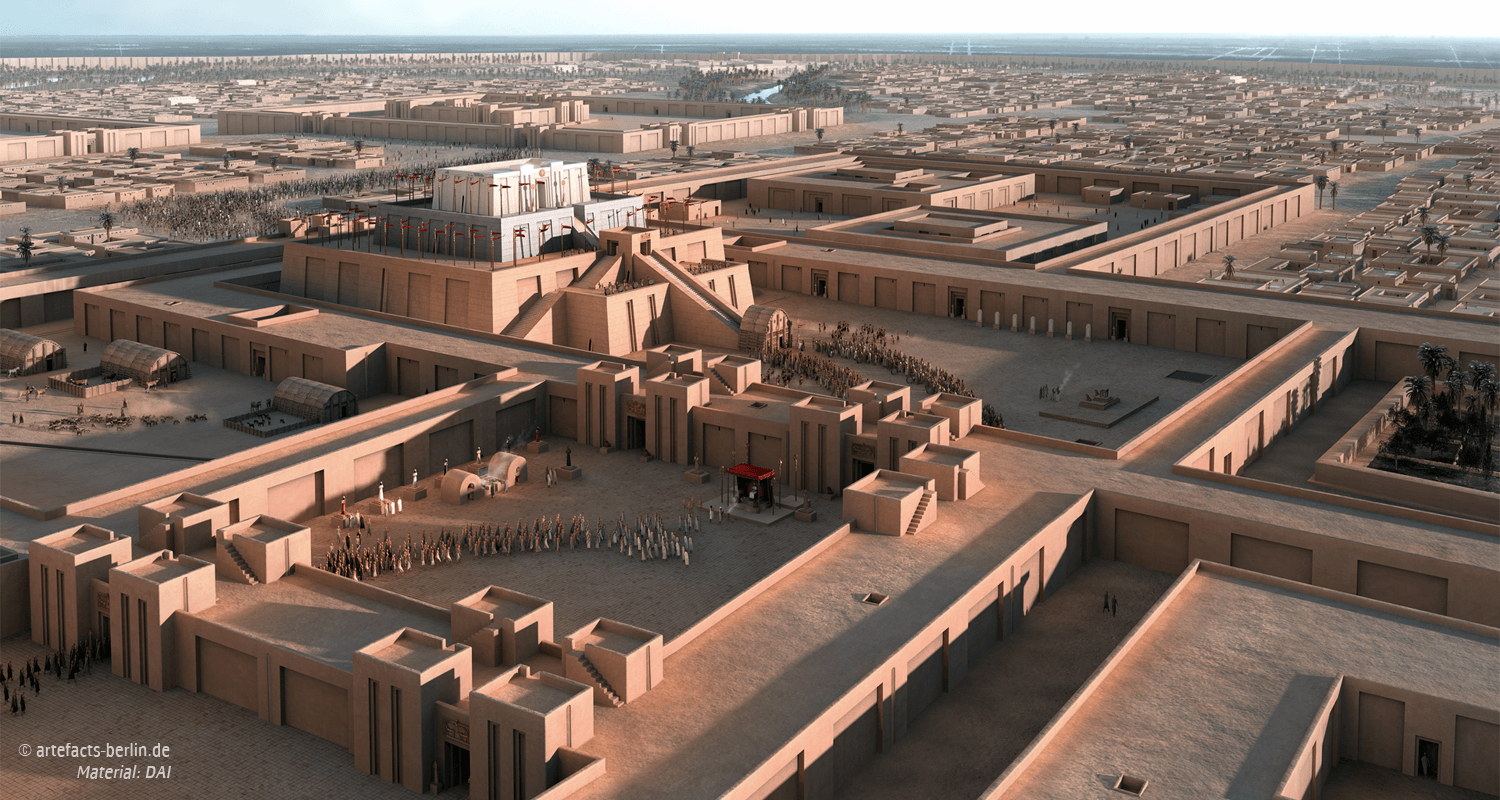

Uruk Machine

The god of heartless market forces

The Uruk Machine gets its name from the “Uruk period” — an era of mass urbanization that took place in Mesopotamia between 4000 – 3100 B.C. Small agricultural villages were transformed into the largest urban center in the world, complete with a bureaucracy, military, and class system. Two years ago, the writer Lou Keep named a new god after this city. The Uruk Machine represents what happens when irreversible market forces collide with pre-industrial social systems. The Machine has authoritarian impulses, and it seems incapable of caring about lifestyles and rituals that don’t add value to the economy. It turns chaotic “messiness” into coherent “order” that can be exploited, creating social unrest wherever it goes. Lou Keep argues that this pattern has repeated itself throughout history:

Smaller units (individuals, communities, etc.) have efficient but localized forms of doing a thing. The doing of the thing is plugged into a much larger worldview which explains both how to do the thing and why you do the thing — James Scott calls that metis. When a larger unit (states, corporations, what have you) subsumes the smaller unit, it tends to uproot metis for efficiency, for raw gain, for humanitarian purposes, etc. Power is weighted heavily in favor of the larger unit, not least because community explanations appear irrational or are otherwise unintelligible. To regain some of that power, communities or groups within them tend to form mass movements. Those then replicate the ill effects of the original larger unit, whether they gain power or not. For various reasons, mass movements tend to sap power from their adherents and frustrate them more. They also tend to prescribe epistemic solutions. In other words, the origin and response tend to exacerbate and blur into one another.

A prototypical example of The Uruk Machine is the story of what happened when the first European settlers tried to make deals with indigenous people. The Native Americans did not have the deeds, titles, surveys, and institutions that proved land ownership to Europeans. In their culture, oral agreements carried more weight than the written word, and they didn’t even think of property as something that could be privately “owned”. But their way of life was invisible to the market that fueled European colonization and later, American “manifest destiny.” As a result, millions of indigenous people ended up getting brutally sacrificed at the hands of the Uruk Machine.

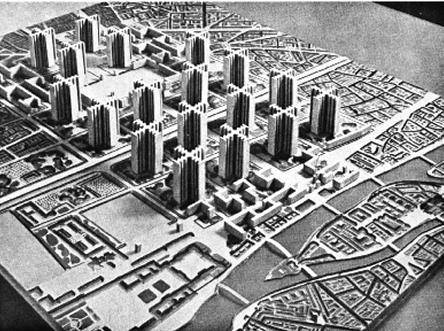

An example of The Uruk Machine in urban planning: Le Corbusier's early 20th century vision to re-design Paris.

In its quest to measure and optimize for a very specific type of economic productivity, the Uruk Machine bulldozes over traditional cultural practices at the expense of our emotional well-being. In fact, the better it gets at collapsing these social relations, the bigger it grows. Today we're left with the damage this god hath wrought: widespread loneliness, disconnection from community, and a mental health crisis. The Uruk Machine has created a seemingly irreversible feedback loop and, like Moloch, it’s a demon that we participate in but can’t seem to control.

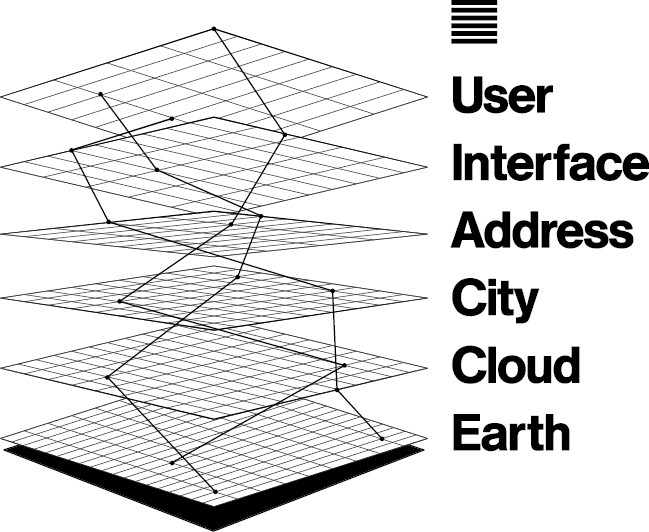

The Stack

The god of systems thinking

This next god is no doubt the most academic and abstract of the 2019 pantheon. It’s called The Stack, and it’s a new framework for understanding modern geopolitics. In the 21st century, we’re very accustomed to 2D maps that show Earth’s territory divided into a jigsaw puzzle of sovereign countries. But these maps have become terribly outdated in an age when global tech platforms are also major political actors on the world stage. The Stack is an attempt to re-present what systems of power actually look like in the modern era. And it’s what you get when a systems thinker tries to create a system to rule all systems — a 3D “megastructure” made up of six layers: earth, cloud, city, address, interface, user. Here’s how MIT Press describes the theory:

Benjamin Bratton proposes that these different genres of computation—smart grids, cloud platforms, mobile apps, smart cities, the Internet of Things, automation—can be seen not as so many species evolving on their own, but as forming a coherent whole: an accidental megastructure called The Stack that is both a computational apparatus and a new governing architecture. We are inside The Stack and it is inside of us.

Unlike the Human Colossus, The Stack is a theory of governance that explores how our political systems might co-evolve with technology in the near future. Whereas the other gods are not subject to our will, Bratton believes that we’ll eventually be able to control The Stack. He claims it’s a neutral description of our world, but I suspect it’s deeply ideological. Bratton says our obsession with subjective human experience has kept us from embracing our evolutionary destiny: fusing our organic bodies with the technological Stack. He hopes we’ll eventually give up on what he calls the myth of human exceptionalism and create a “more reality-based understanding of ourselves.” The Stack is ultimately a technocrat’s dream: a high-fidelity model of the world that’s meant to help theorists and practitioners completely re-design it.

If history is a guide, it’s hard for me to believe that such an abstract image of god will have a long shelf life. It’ll probably suffer the same fate as 19th-century neuroscience theories that claimed the brain is like a super complicated network of telegraphs. The Stack isn’t actively hostile towards humans, it just thinks that we’re relatively irrelevant.

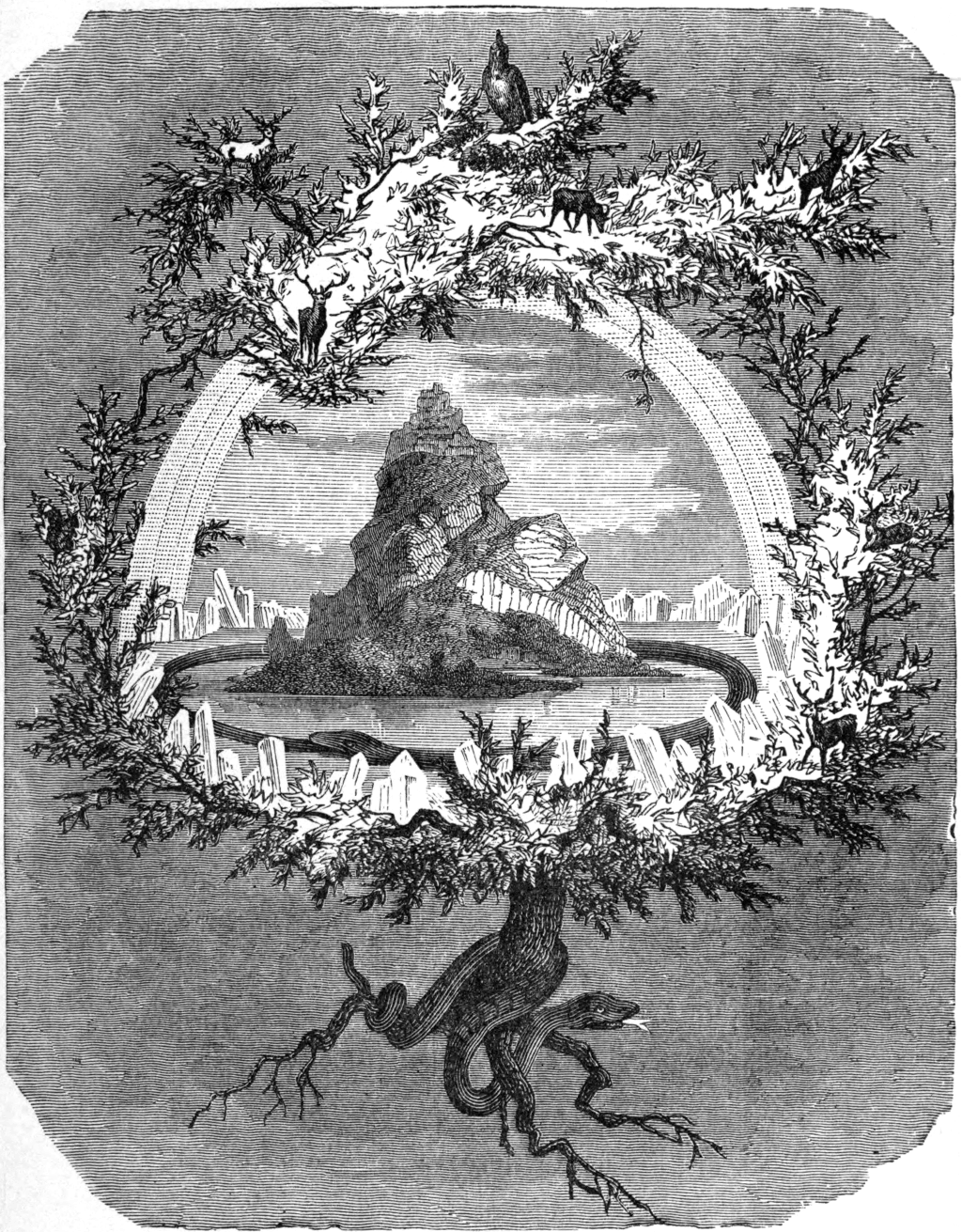

Yggdrasil

The god of spooky entanglement

Unlike the hyper-technological Stack, Yggdrasil is an ecological god that takes the form of a tree. It comes from ancient Norse mythology and was recently revived by Venkatesh Rao in an essay called Think Entangled, Act Spooky. According to the Poetic Edda — a 13th century collection of Icelandic poems — Yggdrasil is a giant holy ash tree with branches that extend all over the cosmos. Venkatesh’s modern rendition of the myth helps us understand that, in our globalized economy, even small local actions have strange and unpredictable ripple effects. It’s like the butterfly effect, but supercharged by the internet and international supply chains.

“Life in Yggradsil,” says Venkatesh, “is entangled in weird, non-local ways. Spooky action at a distance is the rule rather than the exception.” He goes on to explain why today’s world feels “spookier” than ever:

The world has of course, always been entangled and spooky, but while we had a comfortable cushion of cognitive surplus to work with, we could pretend it was simpler than it was by carving it up in ways where concerns and consequences could be made largely local, and causal reasoning could ignore “externalities.”

In an interconnected world, the concept of “externalities” is a short-sighted delusion. Everything is internal. Nothing can be turned into somebody else’s problem or some other species' problem. Our actions boomerang back to haunt us or help us, like the plastic waste that floats inside the fish we eat or the friendly reply to a Twitter thread that turns into a beautiful life-long collaboration. Technologists now make structural decisions that impact the lives of billions of people all over the world. Maybe Yggdrasil could help them remember that their actions will have weird and spooky downstream consequences.

A map of the internet resembles the root system of a tree.

It’s always surprised me that we use “the cloud” as our metaphor for the internet rather than a tree. Yggdrasil sucks our data from the servers at its roots so that we might be able to enjoy its fruits in our feeds.

The Singularity

The god of artificially intelligent utopia

The Singularity is probably the god in our pantheon that’s closest to spawning a full-blown organized religion. The techno-utopian deity has many faithful followers in Silicon Valley who believe that artificial intelligence will soon become smart enough to vanquish Moloch once and for all. All we have to do is keep on improving our AI systems, and eventually they will start improving themselves.

This god already has a number of prophets going mainstream. Ray Kurzweil, a well-known leader of the movement, says that “a historical achievement known as the Singularity will allow humankind to ascend to the next level of evolutionary existence: its inseparable union with artificial intelligence … It will liberate humankind from the organic prison of carbon-based bodies.” There’s also Anthony Levandowski, the infamous former director of Uber’s autonomous vehicle project, who recently started a Singularity Church — complete with worship services and rituals. In a BuzzFeed report written earlier this year, Adam Morris recounts what he learned when he snuck into San Francisco’s Singularity University Global Summit:

I learned that through interplanetary colonization, explorers might acquire resources from other planets, which could meet all human energy needs on Earth … I was able to experience something that years of religious enthusiasm could never conjure: I got to feel what it was like to be surrounded by true believers in a cause that was only valued by an in-crowd, an ascendant elect. Circulating among them, I sensed the presence of that spirit that presides whenever so many ardent believers come together in its name. I could feel souls uplifted.

I’m not the first person to notice that the parallels between Biblical rapture and the technological Singularity are a bit uncanny. Much like Medieval Christians, the Singulitarians make a sharp dualistic distinction between the divine and the merely human — between AI “stuff” and non-AI “stuff” like organic biology and inanimate tools. Adherents are convinced that there will be a moment in the future when humanity is “saved” by a power that’s beyond our comprehension. But we must demonstrate our faith through good works. Singularity believers worship at the altar of their own technological prowess, praying that the AI will be benevolent when their soul is uploaded to Heaven.

Egregore

The god of collective consciousness

Last, but not least is my favorite modern-day god concept. Coined by the 19th-century French poet Victor Hugo, an “egregore” is a collective intelligence that’s created when people come together around a common purpose. A corporate bureaucracy is a type of egregore: it’s distributed across the minds of the many people it employs, but it’s not entirely controlled by any one of them. “Uber takes action to fix unsafe cars”, “The DNC said no to a climate debate.” We know that this is just a manner of speaking — organizations aren’t actually independent entities that make decisions on their own. Or are they?

A corporation is indeed made up of people, but perhaps it makes more sense to think about it as a hive-mind. Using a combination of man-power and computers, corporations can accomplish things that no single person ever could. Sometimes, it even outlives the people who created it. You can’t point to it in physical space because it’s more than just the office building it occupies.

The egregore concept is powerful because it allows us to talk about conspiracies without conspirators — group behavior that appears highly coordinated, even though no one deliberately orchestrated it. Sarah Perry, a writer and astute cultural observer, explains more in her essay Weaponized Sacredness:

Egregoric entities, whether gods or demons or dictators at the center of a cult of personality, are powerful entities, even as they are imaginary — wholly created by and consisting of thoughts, speech, and behaviors. The human mind is a powerful entity, and becomes more powerful in coordination with others. To say that an “imaginary” entity, existing only in human minds, has agency, is not much stranger than suggesting that humans themselves, inscrutable piles of preferences that we are, have agency. Agency is no more than a “quick and dirty way of contextualizing the temporal activities of entropy climbers,” as St. Rev puts it.

While the other gods we’ve explored in this post are all-encompassing, the egregore concept makes room for a plurality of gods. There are as many egregores as there are groups of people. From small cliques to large corporations, egregores come in all shapes and sizes. They interact with one another via human “representatives”, each of whom embody and enact the interests of the egregores they are a part of.

Historically, the most successful egregores have developed a symbiotic relationship with their human hosts. By way of example, Sarah Perry points to the ritualized days of rest found in many organized religions: “Old entities often have a sabbath attached to them, a frequent, repeating time for rest. The sacralization of this time places a hard-to-erode boundary around the demands that can be placed on constituent humans. This may be a way of keeping ‘demands’ within the productive zone, and not triggering the entity’s own demise by demanding too much.”

Unlike ancient deities, however, modern egregores are able to demand more time and energy from their human hosts now that the Uruk Machine has knocked out local social protections like the sabbath. And thanks to the internet, today’s egregores can spread more quickly because they aren’t limited by geography or transportation technology. As a result, we’re witnessing a Cambrian explosion of parasitic egregores, and it remains to be seen whether we can successfully push back.

This leaf-cutter ant colony is like an egregore — it's intelligent enough to create superhighways for transporting leaves, even though no single ant is orchestrating the whole shebang. Source: Our Planet

Resurrecting dead metaphors

Humans are pretty bad at reasoning about complex systems. In the past, our gods and demons allowed us to talk about phenomena that we didn’t fully understand. During the Enlightenment, we tried to kill them and explain everything in reductionist scientific terms. But it feels to me like we’ve come full circle. The great irony is that in our quest to disprove God, we’ve created a world that’s more magical and mysterious than Medieval people could’ve ever imagined.

Our relationship to the 2019 pantheon is not all that different from the way our ancestors related to their gods and demons. We’re back to using oversimplified metaphors to wrap our minds around the uncontrollable complex systems we’re embedded in. The question of whether we truly “believe” in the deities of 2019 is sort of irrelevant. In his book All Things Shining, Hubert Dreyfus explains that most pre-Enlightenment Christians did not actively “choose” to “believe” in the Bible — it was simply the taken-for-granted truth about how their world worked:

Consider the Middle Ages, for example. During this period in the Christian West, a person’s identity was determined by God. To say this is to take no stand on whether there actually was a God in the Middle Ages. The classic metaphysical arguments for the existence of God are irrelevant here. What matters instead is that in the Middle Ages, people could not help but experience themselves as determined or created by God … This order of things was not a belief that anyone argued for or a worldview that anyone proposed; it was simply taken for granted by everyone worth talking or listening to. The way of life of a culture is not an explicit set of beliefs held by the people living in it. It is much deeper than that … it governs the actions of the people in the culture although they are not normally aware of it.

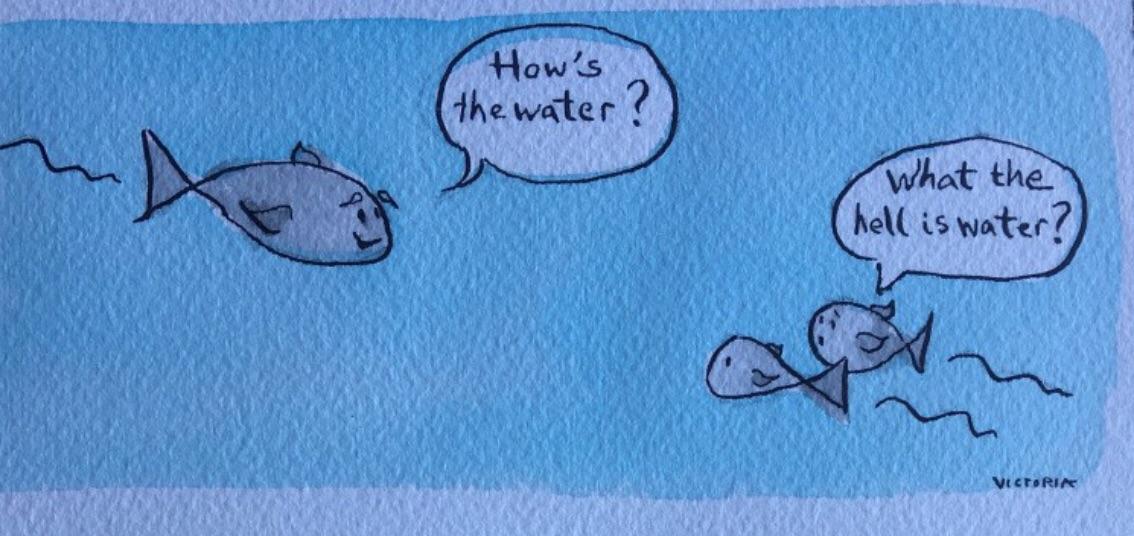

I’ve experienced first-hand what this feels like on the inside. As a kid, I attended Evangelical Christian school from kindergarten through eighth grade, learned about creationism in science class, wrote letters to God in my prayer journal. My bubble of beliefs was basically quarantined from the outside world. I was always surrounded by other Christians, and it was impossible to understand how anyone could not believe in the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. He was everywhere, all-consuming, the invisible background. To my mind, there was no such thing as life “outside” Christianity. It was the water I swam in.

In college, I swapped out my traditional beliefs for Science and “systems thinking.” I no longer felt totally embedded in a world that only God could fully understand. Like the Enlightenment rationalists who came before me, I thought I could see the big picture myself, and the religion of my youth seemed irrelevant. But the more I learn about the “gods” I’m writing about here, the more I understand the purpose of the old “God” metaphor. I couldn’t see what the hell my parents were talking about until I discovered “higher powers” on my own terms — metaphors that resonated with my very secular and scientific 2019 mind. Turns out there was a baby in the bathwater, after all.

You might say that our modern god-like phenomena are totally different than what ancient people had in mind. But even the 2nd century Gnostic Christians understood that the image of God as a big king in the sky was only a metaphor for something that’s impossible to capture in words. According to religious historian Elaine Pagels, Gnostics ridiculed people who thought the kingdom of God was a real place, saying “The one whom most Christians naively worship as creator, God, and Father, is in reality, only the image of the true God … The Kingdom is inside of you, and it is outside of you."

Making fun of all Christians for thinking God is a king is like making fun of rationalists for using a giant bull to represent coordination problems. To be clear: I don’t mean to suggest that the gods of this blog post are essentially the same as the higher powers of old. But they can help us simulate how ancient intellectuals related to their deities. Throughout the ages, leading-edge prophets and philosophers have always tried to describe their gods with the most expansive and relevant metaphors they could muster. There’s a good chance that the pantheon we’re exploring here won’t make any sense to a future society that looks nothing like our own.

we implicitly assume that ancient authors could’ve expressed their metaphors in plain and literal prose if they’d wanted to, but

— 🅐🅩🅛 (@aaronzlewis) June 11, 2019

> if you read primitive utterances you will soon realize that what we call metaphorical speech was the natural mode of expression for early humans

Why should we care about how our ancestors felt toward their god-concepts? Well, unlike the loving Lord of the Gnostics, the gods in this post are fundamentally amoral. They don’t have human-centered values, they’re above and beyond our desires, they seem to “happen” to us against our will. They’re cold, aloof, impersonal. This leaves our society feeling depressed and nihilistic. As @listmouse put it on Twitter: “I feel like the biggest reason people are so sad that no one ever talks about is that we know so much about the problems that face us yet our solutions for those problems have rapidly decreased as we've thrown out magic & old remedies & prayer; there's nothing to bring hope.”

We’re cells in the Human Colossus. We’re caught in the fiery clutches of Moloch. We’re invisible to the Uruk Machine. We’re surrendering our data to The Stack. We’re tangled in Yggdrasil’s roots. We’re uploading ourselves to the Singularity. We’re hosts to increasingly parasitic Egregores.

There’s a tight feedback loop between the gods we believe in and the societies we create, which is why we must take seriously the metaphors we believe by.

We shouldn’t feel helpless in the face of the 2019 pantheon. In fact, the new “gods” ought to give us a bit of hope — they’ve helped us re-discover the old, paradoxical idea that complex systems are simultaneously inside of us and bigger than us. They’re the product of our stories, our drives, our aspirations, our love. With that in mind, I’m frustrated by how much time and energy we waste pretending that we can escape from the systems we’re embedded in. We act like talking heads even in private spaces, trading our personal stories for the hand-me-down hot takes of PR strategists on high. We fall into conversational ruts, we become predictable. And the collective egregore mind gets hollowed out by abstract pundit speak that’s untethered from down-to-earth experiences. We have to supply the mind, or the mind falls apart.

I’ve lived inside many bubbles of belief in my 25 short years: Evangelical Christian, hardcore atheist, techno-utopian. Each time I escaped, I thought I’d finally come to a more accurate understanding of how things really are. Now that I’ve acquainted myself with the pantheon of 2019, I’m feeling ready to leave behind the idea that it’s possible to get a god’s eye view of my world. As Tim Morton says in his book Being Ecological:

How I interpret data will depend on what I think I want to find. How I see myself depends on the kind of person I am. How I interpret things is entangled with prefabricated concepts about what interpreting means. This gives rise to a strange insight, which is that living in a scientific age doesn’t mean you are living in a cold world of objectivity. It means you realize that you can’t achieve escape velocity from your own embeddedness in data interpretation or confirmation bias. We cannot get out.

The process of popping out of bubbles and discovering new ones is a never-ending story. This realization definitely won’t quell my curiosity, but I will move forward with a bit more humility and plenty of deep breaths.

Got questions or comments or criticisms? Please drop them here. You can also check out to read the Twitterverse commentary on this post.

You might also like

Metaphors We Live By: the namesake of this blog post and a mind-expanding book about how the metaphors we use shape the way we understand the world.

A post-secular age: an Are.na channel where I'm collecting all sorts of weird articles and images and videos about cyber religion. If you make an account, you can add stuff too!

The desire for full automation: a beautiful essay about the future of AI, the evolution of meaning, and the uncanny similarities between modern ecological thinking and ancient religious beliefs.

The Liturgists: a thought-provoking podcast, co-hosted by a scientist and a pastor, that explores how religion and science might re-unite in the 21st century.

The use and abuse of witchdoctors for life: an essay by Lou Keep that analyzes witch doctors and magical thinking from a game theoretical perspective.

How We Gather: a Harvard Divinity School report that shows how communities like Soul Cycle and Meetup are functioning as proto religious institutions for disaffected young people.

Gay rites are civil rites: a Slate Star Codex essay that asks whether gay pride parades have accidentally inherited all the trappings of religious ceremony.