Inside the digital sensorium

Last week I spoke at the New_Public festival in an “online park” where designers, urbanists, and artists explored how to create better “digital public spaces”. While preparing for the session I hosted, I started questioning how we came to understand our social media platforms as the “new public square” in the first place. The road to widespread internet adoption was paved with spatial metaphors, which helped non-technical people wrap their heads around this brand new technology. We drove down the information superhighway, we visited cyber space, we navigated to web sites. Software designers were known as digital architects who built virtual places for work and play. We talked about the internet as if it was outside of us — an environment to wander around in, an ocean to surf.

But É. Urcades, one of my favorite technologists on the interwebs, has challenged me to think differently about digital spaces. “websites”, he says, “are absolutely not places or architecture, they are temporary bodies … when you design interfaces you are -literally- designing the sensory organs people use to perceive information — interface design is organ design.” When our organs of perception get augmented by new technologies, we experience subtle shifts in our relationships with each other and with our selves. Throughout the 2010s, some wannabe cyborgs have already undergone extremely invasive procedures to augment their default “hardware”. But if É. Urcades is right, you don’t even need risky surgery to acquire new senses. You just have to turn on your (pocket) computer.

Thirty years into the digital age, it’s safe to say the internet isn’t just an external environment that we travel through or a “public space” that we stroll around in. It’s fully entangled with our nervous systems now, and it has re-shaped our minds in ways that aren’t always easy or comfortable to articulate. This process became even more apparent during 2020 — a year in which screens swallowed the last remaining bits of our “offline” culture and daily lives. I don’t think we’ll be able to create the sort of digital publics that the New_Public festival is aiming towards until we’ve adequately taken stock of what happens within us when we live with the technologies we’ve built.

To that end, I wrote up 8 first-person stories about the new psychologies that have emerged under the influence of digital media. These accounts are based on a number of conversations with internet friends and strangers over the last few years. This is no doubt a small sampling of the subjective experiences that have been created by our software “sense organs.” What other unique sensory configurations are floating around out there, waiting to be discovered? Starting today, I’m opening up a digital hotline in order to find out. You can think of the stories below as the very first submissions to the hotline. Perhaps you’ll even recognize some of the experiences they describe as your own.

from: s3c0ndturkl3@*****.com

subject: Exoskeletal unease

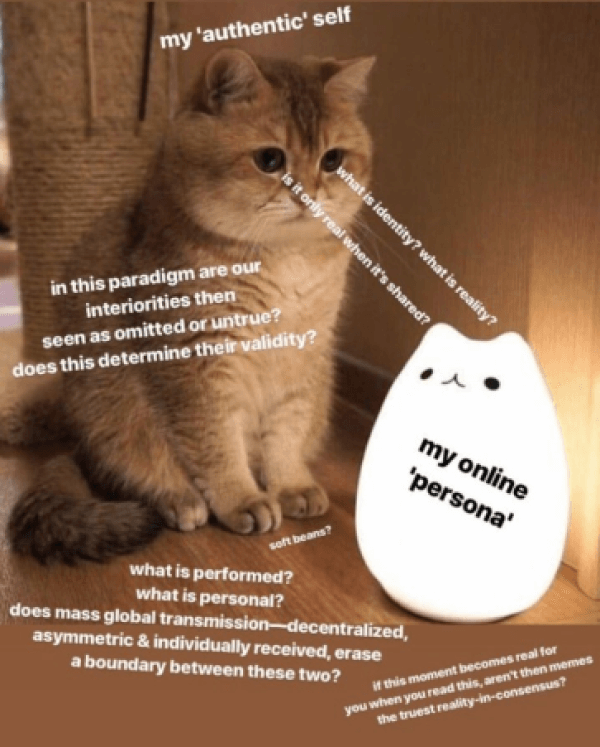

You know that feeling when you outgrow your wardrobe? When you no longer feel like yourself in your old clothes? That happens to me with my virtual avatars and profile photos. Or maybe my accounts are more like exoskeletons that I have to shed as I grow, and they absolutely need to be maintained because they’re as much “me” as anything else. My physical body no longer feels like the “center of gravity” of my identity… my sense of presence is forever fractured and distributed all over the place. I close my eyes and imagine all the screens that are displaying my content at this very moment, I wonder about the total number of pixels I currently occupy, I feel like I am nowhere and also everywhere. After a while, the exoskeleton I wear online doesn’t really feel like a true expression of my inner self. It’s so much work to keep it up to date, but I basically don’t have a choice because that’s where I do most of my socializing nowadays. To be honest, my internet friends are the only people who really understand what I’m about — everyone else is stuck with a shallow, incomplete version of me. As you can probably tell, I pour a lot of my self into these apps. When they die, like Vine did a few years ago, it feels almost like a psychological amputation. I’m permanently cut off from a part of my exoskeleton, and I have to grow a whole new shell.

from: bushyvannevar@*****.com

subject: Hyperlink holism

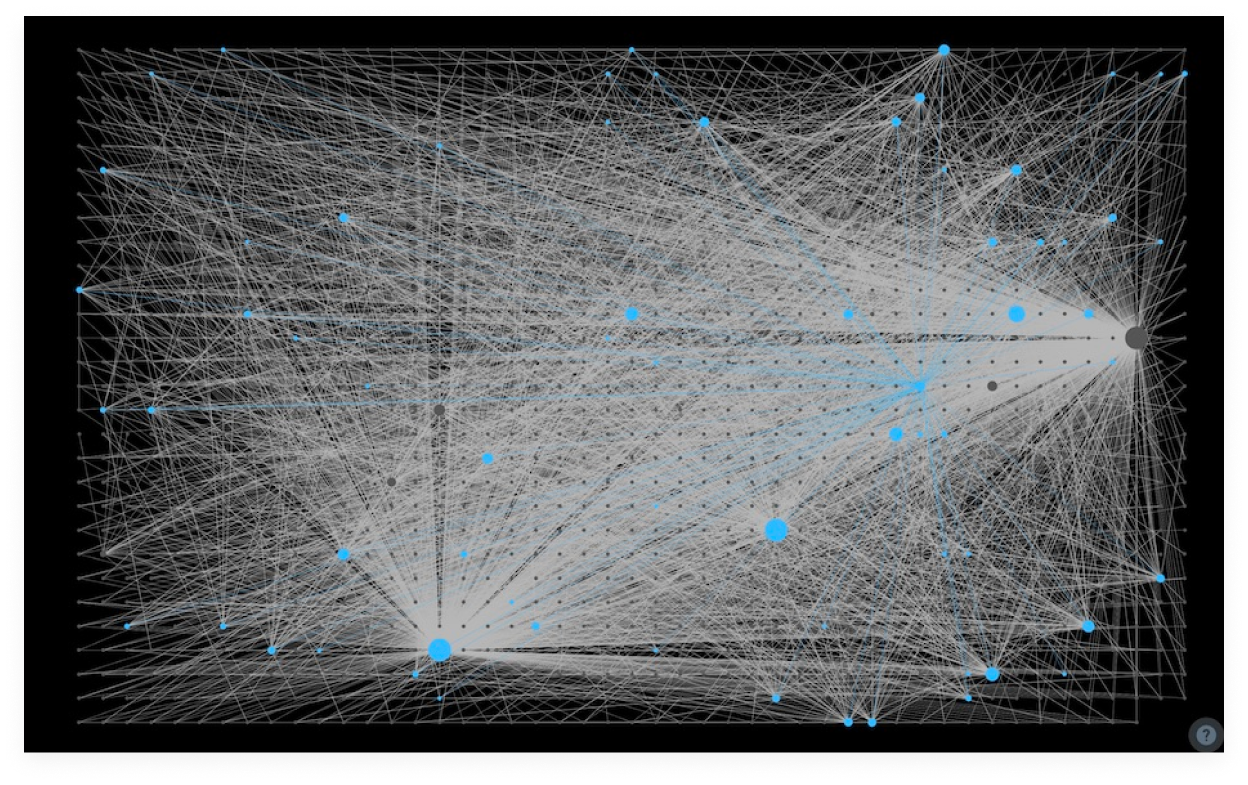

So I started putting together a wiki of all my personal knowledge about 4 years ago, before Roam and Notion and Are.na were even a thing. I really wanted to be able to surf across my own mind the way other people surf across the web. My database is an always-growing network of quotes, speculations, Bible verses, synchronistic hyperlinks, and interesting juxtapositions of information that I’ve collected from all over the place. Now that I’ve been building this wiki for a few years, my perception seems way more hyperlinked than it used to. Any random object or situation gives me like 400 flashbacks to books X, Y, Z and obscure historical references 1, 2, 3. I can’t look at a thing anymore and just see the thing. I filter all new info through the lens of my digitally extended mind and it feels like a superpower, or like that NZT-48 drug from the movie Limitless. Guess you could say I run my own little intelligence agency. Sometimes I even prefer video chat to IRL convos because I can easily reference my external brain without the other person noticing. If I ever lost access to my database, I’m not really sure what I’d do. I think the networked note-takers are really on the front lines of creating the Global Social Computer in the Cloud. Part of me suspects that someday, after I’m gone, someone will be able to use all my data to bring me back to life in deepfake form, like they did to that kid who died in the Parkland shootings. It gives me peace of mind to think that maybe, just maybe, my digital soul will survive into the far future — long after my meatspace body has decomposed.

from: julianjaynes@*****.com

subject: Digital bicameralism

Twitter has definitely changed my relationship with my internal monologue. Just like my vocal cords and larynx turn my silent neural activity into vibrating air molecules, my external voice box on twitter dot com turns my inner rumination into text on someone else’s screen. Before I started posting, my thoughts were more abstract and non-verbal — like blobs of play-doh floating around a zero gravity chamber. I used to spend a lot of time re-molding these amorphous thought forms into Twitter-friendly nuggets. But nowadays my internal monologue speaks tweet by default. Thoughts bubble up from the depths of my psyche readymade for the timeline, already twisted into the pre-programmed shape of a Post. I wonder if the algorithm is starting to interfere with the way my subconscious works. What if it’s filtering out thoughts that it doesn’t think will perform well online? Every day, thousands of strangers upload little slices of their consciousness directly into my mind. My concern is that I’m prone to mistake their thoughts for my own — that some part of me believes I’m only hearing myself think. Sometimes when I wake up in the morning, I’ll scroll through my old posts just to remind myself of myself. It feels like looking in the mirror. I’m swallowing my (digital) self so that I’m me instead of someone else.1

from: realjeanbaudrillard@*****.com

subject: Vidya gaem consciousness

I basically spent all my childhood building worlds in SimCity and Rollercoaster Tycoon and zooming into random cities on Google Earth. These apps definitely inspired my decision to work in urban planning. This might sound weird, but when I walk through a building I can usually tell you what version of AutoCad they used to design it. After spending years and years in rendering software, you sort of get a sixth sense for the tools & features that the architect had access to, and the IRL built environment starts to feel kinda fake — like the different “towns” inside Disney World. On top of that, the POV of the virtual camera follows me out into the “real world.” I’m pretty good at hallucinating what my surroundings would look like from the drone’s eye view. (The other day, one of my friends was telling me that he can convince himself he’s playing The Sims or a first-person shooter game with his own body, monitoring the little green bars, making sure his stats are all good). When I look at the gradient of a beautiful sunset, or the hairline cracks in a concrete sidewalk, or the murky texture of a cumulonimbus cloud, I can’t help but think about how hard it’d be to make something like that in Unity. It’s almost like the world is a big game engine and God is the supernatural renderer. Maybe one of these days I’ll turn around too quickly and spot a glitch. Sometimes I mix up my IRL memories with memories from my VR experiences, but that’s a whole other story…

渋谷でゲームあるある再現してみた pic.twitter.com/dk5KH6kUgM

— がんそ【駒沢アイソレーション】 (@KaoruGans0) August 5, 2020

from: emotional_lisab@*****.com

subject: Mememotions

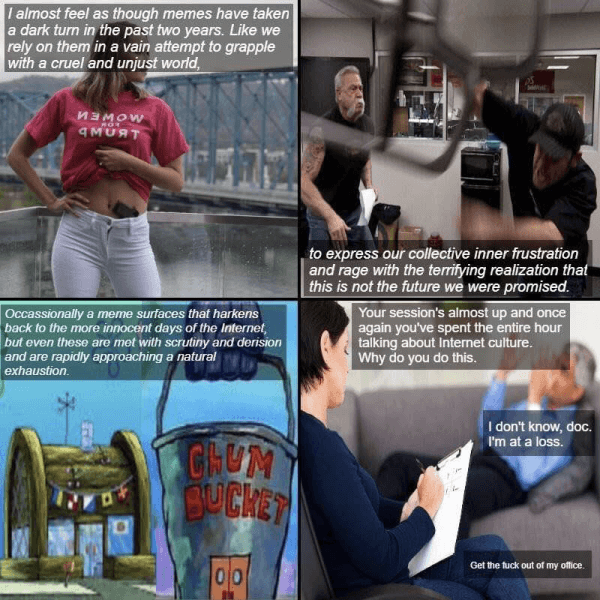

I’ve been on TikTok a lot lately, and it’s kind of changed the way I see and hear things. When I’m scrolling the For You page, I’m not really taking in each video as a whole — I’m always deconstructing it in my mind. I process the audio separately from the visuals and try to figure out how I might re-use the sound for my own content ideas. The weird thing is that this “Song Exploder” mode of hearing has seeped into my everyday life. When I’m out and about, I’m constantly sensing my auditory environment through the TikTok filter in my head. When I’m hanging out with friends who spend a lot of time on the app, we can basically speak a whole different language together. We’ve memorized enough videos that we can have a whole ass conversation using only obscure quotes and dances. It’s a lot more full bodied than regular English. Sometimes I forget how dense the memes are until I try to explain them to my parents and realize that there are layers and layers of references and duets compressed into one 60 second vid. I vibe a lot better with people who are steeped in TikTok culture because the emotions they express are usually based on popular trends, which makes them way easier for me to relate to. I get to be way more performative and flit between a bunch of different characters and POVs and identities without my friends thinking I’m psycho. Love to be in a never-ending improv game.

from: bentham@*****.com

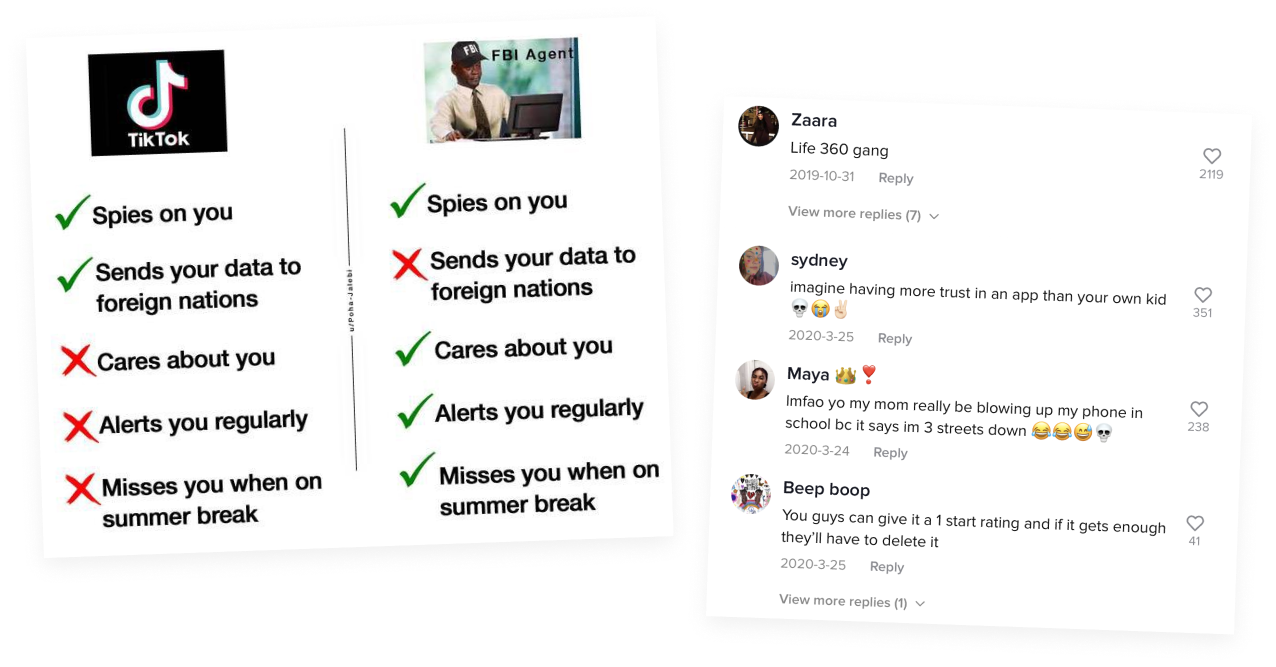

subject: Smartphone shock collar

My dad forced me and all my siblings to download Life360 last summer. He wanted to be able to keep tabs on our whereabouts 24/7. The best way I can describe how I feel is… leashed. I thought getting a phone would make me more independent but it turns out the opposite is true. My mom was always watching my little GPS indicator on her map, making annoying comments about my driving speed, asking nosy questions about where I took the car. I complained to my parents about the app for like 5 or 6 months, and they finally let me get rid of it. But the weird thing is that I somehow still feel like the digital leash is wrapped around me — like there’s an electric fence I’m bound to trigger at any moment. I keep on forgetting that I’m not being tracked anymore. It reminds me of that feeling when you think your phone’s vibrating but it’s just your imagination. Yeah, it’s the lingering sense that I’m being surveilled, even long after I deleted the app. I guess it doesn’t matter if my family’s not watching me anymore — the FBI agent assigned to my case is still following me around everywhere. Sometimes I pretend to flirt with him just to make myself feel better.

from: bergson@*****.com

subject: 4D vision

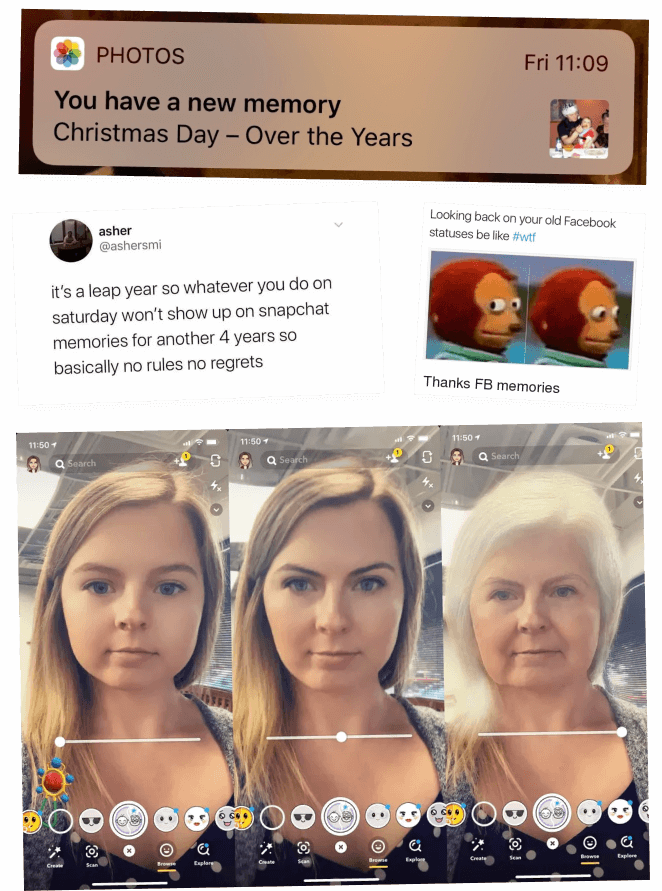

My phone keeps on telling me “you have a new memory.” Snapchat and Facebook are constantly reminding me of “this day in history” — every day, a new arbitrary anniversary. I mean, it’s one thing to open up an old diary by my own choosing. It’s way different when the past is getting push-notificationed down my throat. My biological memory is designed to resurface information from the past that’s relevant to my current situation. But my digitally augmented memory is a dumb nostalgia machine that dispenses pellets of my past to boost engagement numbers. Whenever I take a photo, I’m always thinking about how my future self is going to end up consuming it as a memory.

HD simulations of my past follow me around like a shadow. And my future stares back at me through the Snapchat filter that makes it look like I’m 75 years old. I just feel like it’s becoming really hard to live in the Now. Like, the other day, I went to send a text to a friend that I haven’t talked to in a while. I was expecting a blank canvas, but instead our thread was polluted by an awkward conversation we had 4 years ago. I’m strung out across time, haunted by the ghosts of my old messages, statuses, photos, videos. Another weird thing about social media is that when you change your profile pic, it also changes the profile pic on all your old posts. It’s super jarring to see something I wrote a long time ago right next to a picture of what I look like today. That photo of me next to those words… they aren’t even the same people! Also, my YouTube subscribers consume outdated versions of me, and they always write to me expecting that I’m still the same as I was a few years ago. Time’s out of whack online and everyone knows it — just look at the comments section under any video. People don’t want to know who else is here they want to know who else is now: “Anyone watching in 2021?”

from: skinnerbf@*****.com

subject: Algorithm astrology

Anyone who’s algorithmically connected to me knows that one of my mantras is let the algos be your guide. Everyone’s out here trying to resist the AI, but the truth is that we must ~simply vibe~ with it. Now that I’ve crossed 500k subs, I have a good intuition for what the algo wants from me and where I sit in the constellation of content creators. It’s basically my muse at this point. I can feel the gravitational pull of different topics and aesthetics. Sometimes, I even convince myself that, by feeding the algorithms, I’m contributing to a greater cause: perfecting the invisible intelligence in the sky and helping it see all of us humans a little more clearly. It’s easy to lie to yourself about what you really like and who you really are, but your recommendation algorithms and search history keep you honest. It took me a solid 20 years to figure out that I’m gay but the TikTok algorithm figured it out in like 47 minutes lol. One time I forgot to sign out of YouTube on my parents' Apple TV and after a few days realized they’d been screwing up my recommendations. It was the worst… my whole feed was basically just ‘80s music videos, and it took weeks to flush them all out. When I’m bored and can’t decide what to watch I’ll legit spend an hour rating random movies on Netflix just so it gets to know me a lil better. At this point I can almost smell the demographic labels I’ve been tagged with, and it’s honestly kind of comforting to feel known. Who needs astrology or Myers Briggs when you have all these apps?

Towards truly digital publics

How might these sketches of digital psychology help us create better online publics? Well, I think we have to understand how our private lives have evolved before we can begin to imagine what new publics might look like.

Even though our society has been thoroughly digitized, our mental models of the “public sphere” are still based in large part on the salons, coffee houses, and assemblies of 1700s Europe. I think it’s a mistake to assume that we can (or should) create digital public squares in the image of Enlightenment-era civil society. These now-romanticized forums were made up of individuals whose psychologies were shaped by a totally different media environment — one that revolved around the printing press and its biases. In fact, the very concept of the “public sphere” is so entangled with 18th century print culture that it seems a bit weird to slap the word “digital” in front of it. The newly free presses of this era called the public into being by creating for the first time a large ecosystem of publishers and private readers.2 As media ecologist Paul Grosswiler writes, “print culture favors the linear, detached, abstract, rational, and individual … All of these qualities are encompassed in Habermas’s public sphere, which is created primarily by the press and which furthers critical-rational debate within the newly media-created space of civil society.”

Digitally networked publics are a whole new animal because they’re made up of people whose inner lives have merged with software. Social media users have access to different ways of sensing, interacting, coordinating, and knowing;3 and the experience of the self that emerges from this technologically-enchanted environment is far more porous. If the private sphere has been thoroughly altered by our software sense organs, we should expect that new publics will look a lot more messy and weird than the ones that came before.4 How might the people we met in this post want to gather and communicate — the note taker who feels incomplete without his extended mind, the algorithmic astrologer who treats the recommendation AI as a muse, and the urban planner who feels most comfortable in the disembodied drone’s eye view of things?

We can’t work backwards from a literary notion of “public space” and hope that digital people can somehow be flattened to fit into this old, familiar shape. Instead, we should figure out how to embrace and adapt to the expansive mindscapes that I’ve started to document in this post. Public spaces are never just neutral containers or non-ideological backdrops for conversation. They’re always designed for an imagined “default participant”, and they play a big role in determining what kinds of communication can unfold. This is even more true of digital public spaces because they replace our physical bodies with cursors, keyboards, and avatars whose abilities are constrained by the decisions of designers and developers. As Toby Shorin put it, “different overall metaphors of action” are required.

In order to figure out what these metaphors of action might look like, sound like, smell like, taste like — I think we first need a better understanding of the quirky particularities of the digital “private sphere”. If you want to help, click here to submit your digital psychology story to the sensorium hotline or leave a voicemail at 224-324-4539. I’ll put together a collection of the stories I receive, and together we can start to regenerate publics in a way that’s rooted in a deep, nuanced understanding of what it means to be a self in the digital age.

I’m super grateful to Josh Morin and Andrew Kortina for looking at drafts of this post, and to my Dad for providing a much-needed Boomer perspective. Thanks also to the New_Public Festival, Reggie James, Chris Beiser, and the Other Internet squad for inspiring a lot of the ideas here. If you want to explore the netherworld of digital psychology, check out my Are.na channel, “wtf is digital selfhood”.

-

Via a conversation with @HipCityReg↩

-

In The Gutenberg Galaxy, McLuhan writes that, before the 18th century, “There was no reading public in our sense … Even if literacy were universal, under manuscript conditions an author would still have no public. An advanced scientist today has no public. He has a few friends and colleagues with whom he talks about his work. What we need to have in mind is that the manuscript book was slow to read and slow to move or be circulated.”↩

-

We saw this on full display last week when a Viking-clad protestor posed triumphantly in the Senate. For him, the true seat of power is not actually in that public building — it’s online. The Capitol was merely an expensive studio for producing memes. There are now countless examples of the surprisingly tight feedback loop between digital worlds and our experience of the built environment, and Drew Austin has explored them in depth. See also: Instagram museums and restaurants, the Airspace aesthetic, and ghost kitchens. ↩

-

Digital seems to be confusing the boundary between private and public in a way that re-calls the media environment of the 1600s. Rachel Scarborough King: “17th century letters confound many of our distinctions between private and public, domestic and commercial, feminine and masculine, and fictional and factual documents. Indeed, such dichotomies are largely anachronistic to this period, and one of the ways in which they began to emerge was through extensive discussion of the role of letters in news communications.”↩