Smartphones, superstition, and the postmodern condition

Did we stop trying to make potions or did we figure out how to make potions?

—Agness Callard

Last week, someone discovered the worst software bug I’ve ever heard of. For a few hours, it was trivially easy to turn anyone’s iPhone into a remote surveillance device. Call a friend on FaceTime, press a few buttons, and you could get a live audio or video feed from their phone. This little bug was the cherry on top of our very large techno-pessimistic cake. From Snowden’s whistle-blowing to Zuckerberg’s congressional testifying, we’ve experienced a steady drip-drip-drip of weird revelations over the last few years. They’ve confirmed some of our worst superstitions about Big Brother.

Despite everything we’ve learned about surveillance tech, I still feel weird talking about it in public. There’s a bit of a stigma around taking surveillance too seriously. You can joke about Black Mirror or light-heartedly admit that Alexa is probably listening to your every word. But if you actually make the effort to preserve your privacy, people treat you strangely. As far as I can tell, apathy is the only socially acceptable response. Serious attempts to protect your data are dismissed as excessively paranoid or hopelessly futile. (At worst, they’re perceived as a sign that you have something to hide.) Sure, you can acknowledge the problem, but actual behavior change is a step too far.

How many people will ditch their iPhones for a flip phone because of the FaceTime bug? How many people stopped using Facebook after the Cambridge Analytica scandal? The pundits say that people are lazy, that they prefer convenience, that they don’t actually care about privacy. But I wonder if there’s something deeper going on here.

Superstition redux

Humans have always been superstitious creatures. We pattern match. We look for causes in mysterious places. We crave supernatural explanations for things that are beyond our control. For most of our history, this was a pretty normal way of thinking about the world. People often lived in fear of gods who were watching their every move. This fear could be totally and completely debilitating.

Then along came the Enlightenment. Baruch Spinoza is considered the first modern philosopher who dared criticize superstition publicly in his Tractus Theologico-Politicus. “By separating faith from reason and from making religions' role in the public realm subordinate to that of the state, Spinoza tried to sanitize religion of its pernicious superstitious aspects.”1 Spinoza and his fellow Enlightenment philosophers gave birth to rationalism, empiricism, skepticism, and the scientific method. Supernatural superstitions gradually became taboo, and far-out mystical ideas were relegated to the status of cults or mental illness.

By the nineteenth century, European intellectuals no longer saw the practice of magic through the framework of sin and instead regarded magical practices and beliefs as “an aberrational mode of thought antithetical to the dominant cultural logic — a sign of psychological impairment and marker of racial or cultural inferiority.”2

This dismissive attitude towards mystical thinking is, of course, still with us today. Here lies our postmodern confusion: God is Dead and superstition is taboo, but the companies we’ve created are just as powerful as the gods we once feared. We didn’t stop trying to cast magical spells — we succeeded. You can talk to the dead, summon cars with your voice, instantly send your thoughts to the other side of the world. There’s a “cloud” in the “sky” that can track your location, listen to your every word, know what you’re reading, who you’re dating, etc. Sounds like a god to me.

We like to think of ourselves as scientifically-minded, but most of us have very little idea how our tech actually works. Reality has a surprising amount of detail. For instance, here’s an in-depth overview of everything that happens when you type “google.com” into your browser. Our folk explanations of technology are not so different from, say, ancient descriptions of farming. We lean heavily on anthropomorphized metaphors and fill in the gaps with appeals to authority.

De-pathalogizing Paranoia

Our social norms and taboos around superstition haven’t caught up to our Big Brother reality. We are children of the Enlightenment, and so we instinctively treat privacy fanatics like paranoid mystics. They remind us of the “primitive” irrational types who were supposed to have been “reformed” by Science. We know that concerns about Facebook and the NSA are valid in theory, but we have trouble taking action in practice because it all feels like an other-worldly myth. We find ourselves face-to-face with god-like systems, and we’re crippled by our own rationalism. We choose apathy — yes, because it’s convenient, but also because reality is simply too mystical for our Enlightenment tastes. It’s not surprising that our conversation about tech ethics has been so focused on screen time and FOMO-induced depression. This is the lower-hanging fruit that distracts us from the truly crazy stuff that we don’t yet know how to make sense of — the stuff that makes us feel primitive and powerless.

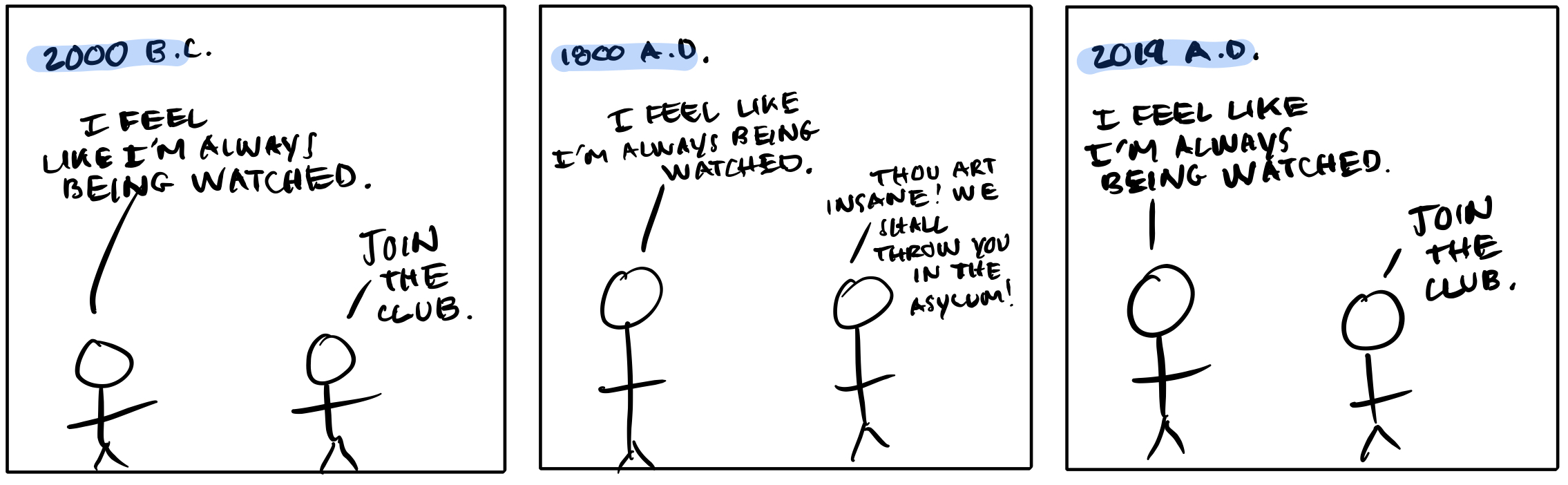

In the not-so-distant past, we diagnosed people who feared they were always being watched with paranoid schizophrenia. Now, that same fear is just a realistic understanding of how the world works. What are we to make of this shift? We don’t yet have a good word for the sober, sane, and concerned understanding of modern-day surveillance. But we should do our best to de-pathologize the passion for privacy. Paranoia, the concept we reach for by default, is far too clinical. Its psychiatric baggage does us more harm than good. It unfairly implies the presence of delusion or blurry thinking. Why can’t it be more normal to be weirded out by the magical powers of our newfound gods?

That said, I realize I’m probably fighting a losing battle here. To borrow a phrase from Venkatesh Rao, technological progress is the art of turning the incomprehensible into the arbitrary. Judging by my Twitter feed, most people have already stopped talking about the FaceTime bug. Last week, my phone could be remotely wiretapped by anyone who wanted to listen in on (or watch) my life. No big deal, though. Onto the next one.

If you liked this post, click here to share your thoughts.

Further reading

“Big other: surveillance capitalism and the prospects of an information civilization”. An examination of the nature and consequences of surveillance capitalism and the global architecture of computer mediation upon which it depends.

Technology as Magic: The Triumph of the Irrational. On the history of magic and the blurry line between our perceptions of technology and wizardry.

“Technology and Magic”. Technical innovations occur not as the result of attempts to supply wants, but in the course of attempts to realize technical feats heretofore considered ‘magical.’