Re: Come for the network, pay for the tool

A public response to an essay by Toby Shorin.

Toby — “Come for the network, pay for the tool” is an awesome piece about digital communities and the rise of de-centralized governance models. Here’s the money quote, in my humble opinion:

Because the mainstream social networks have been designed by a tiny number of people, we have been prevented from experimenting and creating new knowledge about what sustainable community management online looks like. Start erasing the line between operators, customers, and community members disappears, and squint; you begin make out the shape of a group of people who can build for themselves and determine their own path of development.

The digital community organizing that you describe in your post seems like a more sober-minded rendition of the Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace (which John Perry Barlow apparently wrote while he was drunk). The internet is clearly shifting the balance of power, but it hasn’t led to the moneyless disembodied utopia he envisioned. Barlow said, “Your legal concepts of property, expression, identity, movement, and context do not apply to us. They are all based on matter, and there is no matter here … Ours is a world that is both everywhere and nowhere, but it is not where bodies live.” This idealistic dream brings to mind Marc Andreessen’s recent confession that the “original sin” of the internet was not building a payments layer into the browser. The paid communities you investigate are an attempt to remedy that sin and ground cyberspace in the material/economic systems that support our livelihoods.

I want to share some loosely connected reflections about online communities and how they might interact with legacy governance structures in the future. Topics on the docket: distributed universities, hype houses, Kanye’s charter city, the political “grain” of online platforms, Silicon Valley’s desire to “disrupt” the nation-state, and digital localism.

⁂

A few months ago, I decided to run an “ephemeral book club” on Telegram. The experiment was inspired by Krish Khubchand’s Great Thoughts Friday group chat — a pop-up “social network” for discussing wild ideas that expires after 24 hours. Some thirty people responded to my open invitation to read and chat about The Rise of Universities. There was very little structure or scheduling, just a group thread where people shared reactions and reflections about the book. After a month, it became a read-only time capsule of our discoveries.

Together, we dug into the history of higher ed and also experimented with a new(er) form of learning — a discussion forum not unlike the “education and practitioner networks” you outline in your post:

We’re seeing a lot of new venture funded education communities, but here once more is a reason to be more excited about bottom-up community-driven businesses. What happens when groups of independent teachers or consultants who already chatting have shared interfaces to formalize, quote, and invoice? In the past, guilds have provided excellent education opportunities, and they can again.

In The Rise of Universities, I found out that the word “university” originally referred to any group of people who came together for the purpose of learning. Not a building, not an accredited institution, not a system of professors and students. Just any old group of people. The universities of the 12th century had very little in common with the top-down corporate models of today’s higher education. These universities were more like student unions. They were initially a means of protection against profiteering landlords, who would often raise rent as large groups of students moved in. United, students could threaten to leave if the rent got too damn high. And there were many examples of such migrations. “Universities” were free to move because they had no buildings or assets to speak of.

Back then, professors lived wholly off payment from students. If a professor failed to secure an audience of five or more for a regular lecture, they were fined by the students for not being interesting enough! In short, the power dynamics were totally different than what we’re used to. But the perfect storm of Covid + internet + infrastructure for paid communities is throwing us back to older ways of organizing society. In the group chat for our pop-up book club, Krish wrote:

This is kinda similar to the corona-uni context we live in right now; the cost of ‘exit’ is far lower, I see no reason why a similar, digitally native institution for student collective bargaining can’t arise today (esp w next year’s lectures being moved online) … I see a parallel between the professor:administrator:student trifecta and the creditor:financial-intermediary:borrower trifecta, which increases my excitement for the idea of dis-intermediating the process of higher-Ed, or at least re-intermediating it in better ways.

In the 2020s, we are once again building “universities” — in the medieval sense of the term. There are roving bands of people with little-to-no infrastructure or assets. They can migrate fairly easily between tools if the rent gets too high. (I’m reminded of how the Interintellect moved its 300+ members from Slack → Mattermost after they hit the free tier’s limit). And thanks to the No Code movement, it will probably become easier for non-technical people to roll their own solutions and create digital villages that meet their particular needs.

Today’s educational institutions are a far cry from the motley, nimble crews of the 12th century. They’ve grown and ossified into massively bureaucratic administrative states. Such is the life cycle of institutions: they start as scrappy groups of people and then solidify into lumbering giants. Most institutions are not designed to die — immortality is the goal. The assumption is that they’ll live on for as long as possible. But this is just death denial at scale. All systems need some kind of turnover or life cycle if they want to remain relevant and vibrant. What if communities were designed with an expiration date in mind? Some kind of agreed-upon mechanism for renewal or reshuffling, the way legislation and patents expire after a certain amount of time. More like a living organism than a piece of plastic.

⁂

Last year, Venkatesh Rao wrote a piece called “politically opinionated platforms”, where he argued that a platform-scale social technology is basically a political ideology. Its design dictates a particular political “grain”. AR and VR, for example, are libertarian left because they democratize production tools and encourage individuals to create new realities. In a similar vein, Peter Thiel often says “crypto is libertarian, AI is communist.”

Democratized production tools tend to encourage individualist divergence driven by creative effort and personal growth. There's a reason creative/artistic communities lean left-libertarian. Creative tool-use at once encourages individuation and social connection driven by openness to experience, novelty-seeking, and diversity-seeking.

Venkatesh argues that, unlike MySpace, Friendster, etc., the current generation of platforms has figured out longevity and are here to stay. They’re city-states that will keep on changing with the times. And they’ll evolve like rainforests, not fruit flies. Maybe the new crop of “paid communities” is like the underbrush and fungal networks that support the health of the entire ecosystem.

I’m personally really curious about the political orientation of these new de-centralized networks. Not their ideological beliefs, per se, but whether they’re pointing towards “transcendence” or “immanence” — in other words, are they Phillip K. Dick style gnostics who want to escape their bodies and upload their consciousnesses to the Cloud? Or are they down-to-Earth ecologists who include their local contexts and their bodily senses in their sense of self? Some sort of hybrid or combination?

It seems like a fundamental (but often unspoken) political question of the 2020s is: to what extent are we OK with accelerating into the digital realm and leaving the IRL material world behind? This debate is perhaps best exemplified by the controversy over a tweet from the venture capitalist @balajis about “physical social distancing, digital social networking.”

One possible good future

— balajis.com (@balajis) May 11, 2020

- move out to rural area

- work remote

- change jobs more easily in a truly global labor market

- fewer but longer drives with autonomous cars

- 24/7 delivery drones

- socialize online & in VR

Physical social distancing, digital social networking?

A lot of tech enthusiasts seem to believe that we should dive head-first into the social singularity. As the world of microbes and viruses gets increasingly dangerous, they’d prefer that more and more of our reality is mediated by digital interfaces. This is the world of dystopias like Ready Player One and the WALL•E space ship. It’s also the world of anything-goes VR utopias, where you can be whatever you want to be and escape the limitations of your body and its default form-factor. Some of the paid communities you describe are more oriented towards the Balaji’s “good future”: entertainment and fandoms, fantasy sports, streamer communities. Others are more oriented towards the trad IRL: education and practitioners, communities that govern things, small-scale political community organizing and mutual aid, neo-monasteries like the Monastic Academy.

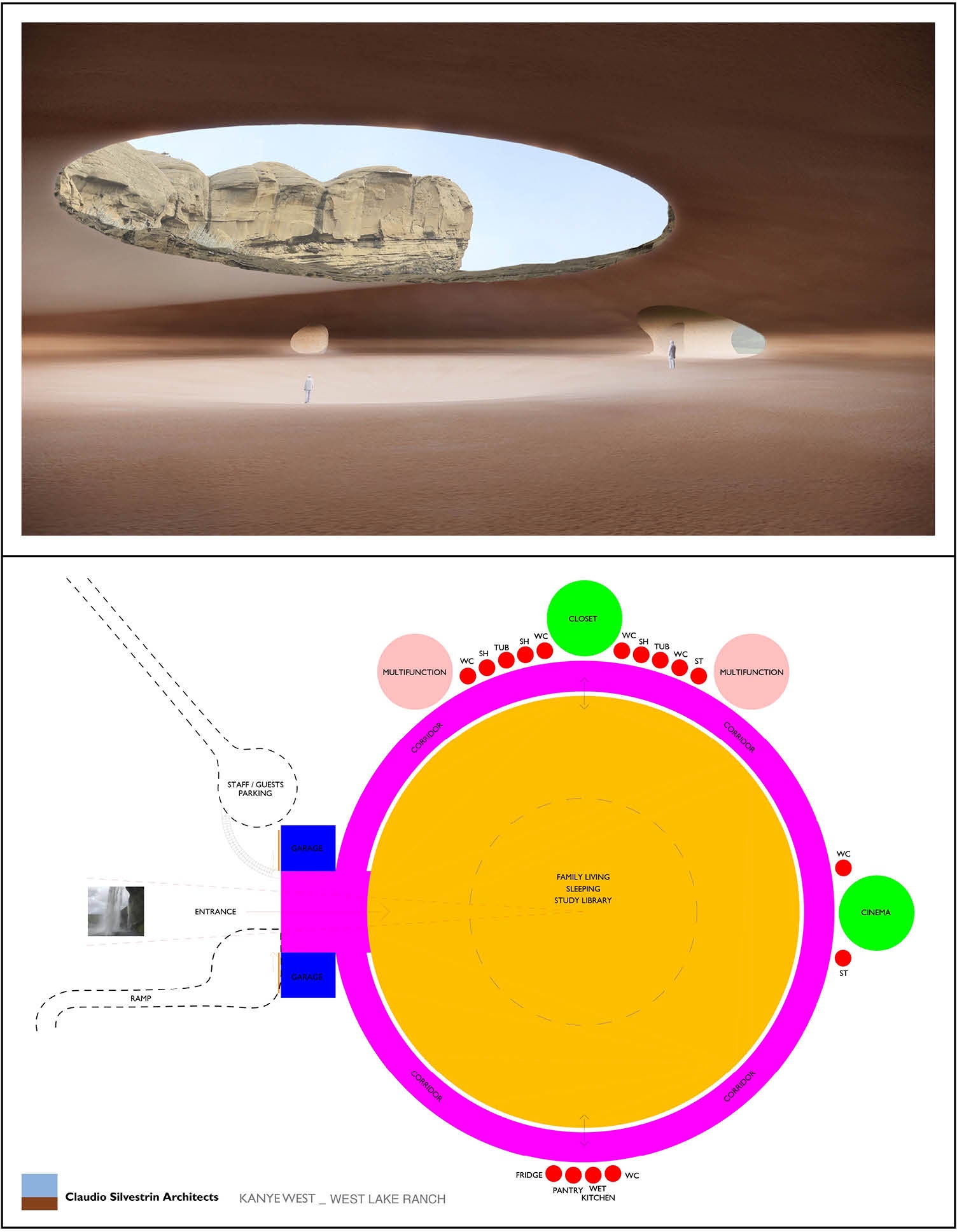

At the most extreme end of the IRL community spectrum, you have things like Kanye’s cult-commune-charter city in Cody, Wyoming — a retreat center and school and 100,000-person circular amphitheater for Sunday Service concerts. It’s basically a hype house writ large. A feudal mini-state created by one of the biggest attention aggregators in the world. WATCH THE THRONE, indeed.

Architectural mockups for Kanye's paid community.

⁂

I think a lot about how many people feel more attachment to their digital community than their state or their town. LARPers participate in their “fictional” worlds with more passion than a lot of Americans participate in their local democracies. Fandom ate the world and created new models of “citizenship”. Subscriptions are like the new “taxes” or “tithes”. It feels good to be highly engaged in a digital environment because it’s way easier to contribute to the story, cast a vote, shape the narrative. Digital communities feel more alive and involved than geographic constituencies. But I worry about disengagement from the political structures that support all of this digital infrastructure.

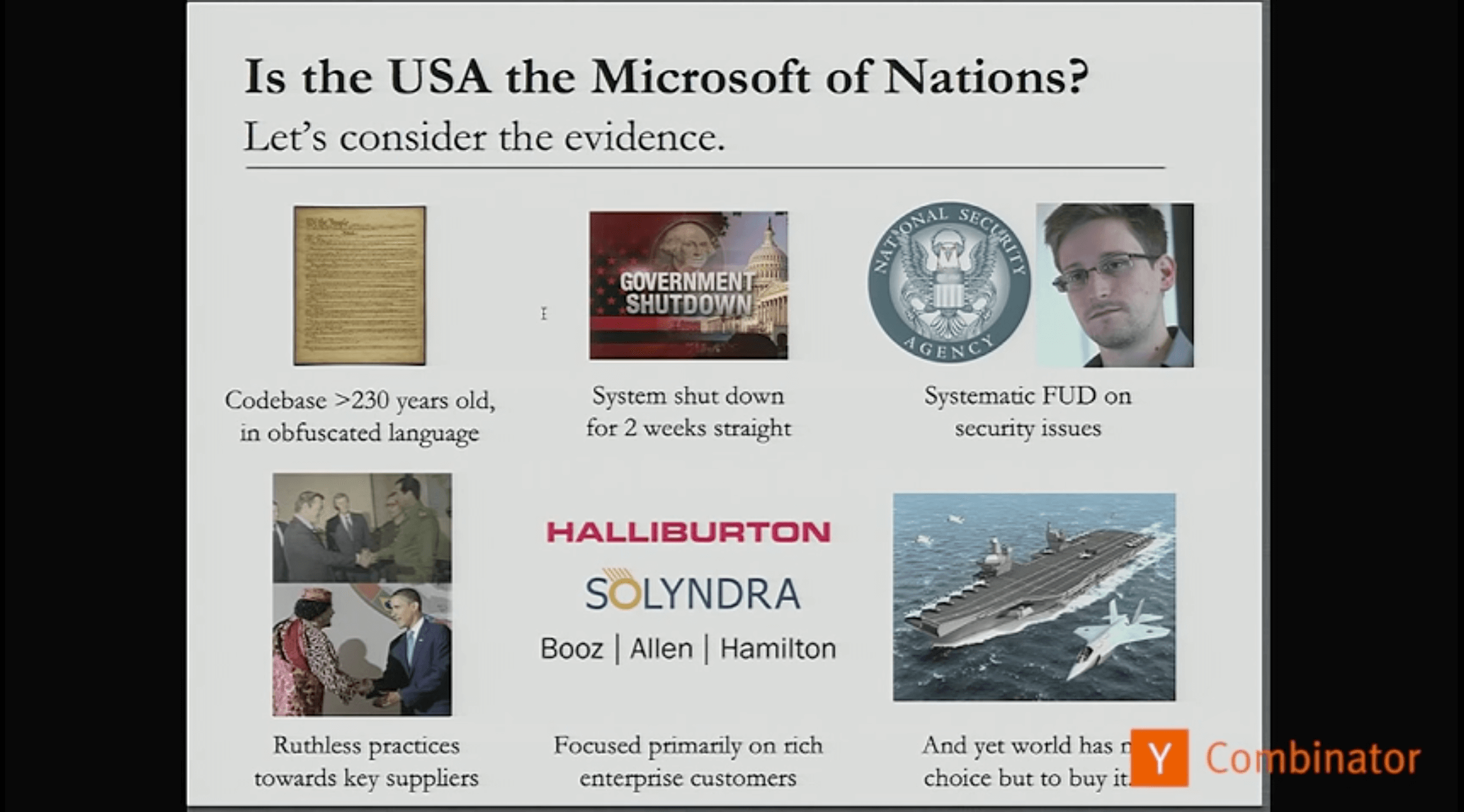

One possibility is that these digital communities try to stage an exit from old-school political institutions. Incidentally, this is what Balaji proposes in his 2013 Y Combinator talk: “Silicon Valley’s ultimate exit.” I definitely understand his frustration with the powers that be. He argues that the U.S. is the “Microsoft of nations” and that tech people ought to be able to exit the nation-state just as budding entrepreneurs exited Microsoft in order to start something new: “I believe that the ability to reduce the importance of decisions made in D.C. is going to become increasingly important over the next 10 years.” Balaji also wants to make geography and physical location less relevant. “There’s this entire digital world up here that we can jack our brains into and opt out,” he says. Last year, I heard a Facebook exec refer to this process as “boiling the Westphalian frog.”

See also: Balaji’s tweet from yesterday about knitting together independent newsletters into a new kind of de-centralized media entity. “Come for the newsletter, stay for the network?” he asks — perhaps a nod to your essay.

A still from Balaji's talk about exiting the nation state.

I once asked the Twitter hivemind if an internet community will ever try to get political representation in government (because Very Online people often identify more with their digital tribe than their congressional district). Or maybe they’ll forego traditional institutions and set up social systems in virtual worlds. @micahstubbs responded with an interesting quote about the hollowing out of the Holy Roman Empire: “Having learned from experience that there was not much to gain from active and costly participation in the Imperial Diet’s proceedings due to the lack of empathy of the princes, the cities made little use of their representation in that body.” We all know how that story ends.

What will happen to the virtual realm if we continue to neglect the environment that sustains the brains that are jacking into the Matrix? As you and I both know, these digital networks are not really “non-physical”. And it seems like the global supply chain and infrastructure that supports digital consciousness is not actually sustainable over the medium to long-term. Are these online paid communities building houses on sand? I feel a little weird asking this out loud because the ecological crisis is not usually included in conversations about the future of digital media.

Despite my hesitations about uploading society to the metaverse, I’m feeling hype about the transition you outline at the end of your essay:

We are transitioning from an era of centralized management of human development and financial capital into an era where both identity formation and resource allocation happens in decentralized, loosely-coordinated, and emergent ways. I think we will gain the most learnings about the future of business and identity not from top-down corporate models of community management, but from friends, squads, and content creators starting groups and supporting the legitimate participation of community members in their ongoing development, finance, and governance.

My hope is that we can restore and sustain some kind of feedback loop between communities in the clouds and communities that are tied to land and geography. That we can use what we learn about community organizing in digital spaces to re-animate our localities and our bio-regions. Douglas Rushkoff calls this digital distributism; Ezio Manzini calls this Slow, Open, Local, and Connected. I don’t know what the right solutions are here, but I’m definitely excited to experiment.

A small but beautiful example is Austin Wade Smith’s Digital Animism Club. The web site speaks in the first person, saying: “I’m a little server. I live at 366 Devoe St, Brooklyn New York … I run on solar power, so I get tired occasionally and dont feel like working that day.”

The home page of the Digital Animism Club.

Another example I stumbled upon recently: Hylo, “a free open-source collaboration platform designed to help communities thrive.” It bills itself as an easy way to organize and grow a community. Groups like the Buckminster Fuller Institute and the Planetary Health Alliance are apparently using it for network building and regeneration projects. There’s also Epsilon Theory — a narrative economics blog with over 100,000 members that’s trying to rehabilitate broken institutions from the bottom-up. Ben Hunt, its founder, encourages his subscribers to start their own local chapters, connect with other readers, and organize local political action.

I wonder how we can help the generation that grew up on Minecraft get as excited about re-animating their physical environments as they are about improving their virtual worlds. A Nikita S. tweet comes to mind: “One of the magical things about a childhood spent in simulated worlds where the rules of behavior and of the universe are easily broken (and sometimes rewarded), is that the ‘rules’ / existing system in the real world appear more fungible. Kids break shit, try new methods.” I think about all the villages I built in The Sims and the communities I brought together on RuneScape and the parks I designed in Rollercoaster Tycoon. Surely these skills are transferrable, if only they had an outlet.